LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – This week in history features the story of the naming of American towns and how Thomas Jefferson, great statesman and imminent writer, was a horrible at it.

April 23, 1784

If you have spent any length of time driving through our beautiful country you will be amazed by the creative flair American pioneers used to name the dusty towns they settled.

Sometimes a name would embody the spirit in which the town was founded: New Era, Michigan; Inspiration, Arizona; Excel, Alabama.

Other times a famous man would lend his name to a town: Tolstoy, South Dakota; Napoleonville, Louisiana; Ringling, Oklahoma.

A favorite was to evoke the virtues of a past (or present) President, in a fit of patriotic zeal. President James Polk gave his name to towns and/or counties in Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Iowa, Minnesota, Missouri, Nebraska, North Carolina, Oregon, Tennessee, Texas and Wisconsin.

At yet other times, since America has always been a country of immigrants we’ve peppered our nation’s atlas with the names of foreign towns: Paris, Texas; New Madrid, Missouri; Holland, Michigan.

Then there are those names that could only have been conceived in the spur of the moment. Ong’s Hat, New Jersey was supposedly so named for a dancer and ladies’ man, Jacob Ong, who regularly attended Saturday night dances with a shiny hat perfectly perched atop his head.

One evening he neglected to pay attention to a certain young woman who, frustrated at being spurned, grabbed Mr. Ong’s hat, threw it on the ground and stomped it out of shape.

Eighty Eight, Kentucky got its name because it is located 8.8 miles away from the county seat of Glasgow (another foreign town name, in case you’re keeping count).

Before you laugh, you should remember that our very own Middletown was so named, supposedly, because it was midway along the stage line between Calistoga and Lower Lake!

Perhaps the most desultory name in America goes to Why, Arizona. When asked why they chose that name for their town, the town elders exclaimed “because we couldn’t figure out why people would want to live here!”

There are names that came about because something was lost in translation. Embarrass, Wisconsin was named first by the French trappers who noticed that the stretch of river alongside which a town would later be built consistently trapped the logs that were floated down to sawmills.

Riviére Embarrassé, or “Tangled River,” the French called it and American settlers mangled it to “Embarrass,” for which we ought to be.

Worse than Embarrass, Wisconsin is Smackover, Arkansas. Seeing that the area around was covered in sumac shrubs, the French trappers and hunters from nearby Louisiana called the area Sumac-couvert, or “Sumac Covered.” If you say it quickly and often enough, it does start to sound like “Smackover” I suppose. Apparently we Americans don’t do well with French.

Perhaps the king of quirky naming goes to our third president, Thomas Jefferson.

Before most of these aforementioned towns were settled, indeed before most of these states were even founded, Thomas Jefferson had a chance to leave his mark on the country’s map. Thankfully for those people who now call the Midwest their home, Jefferson failed.

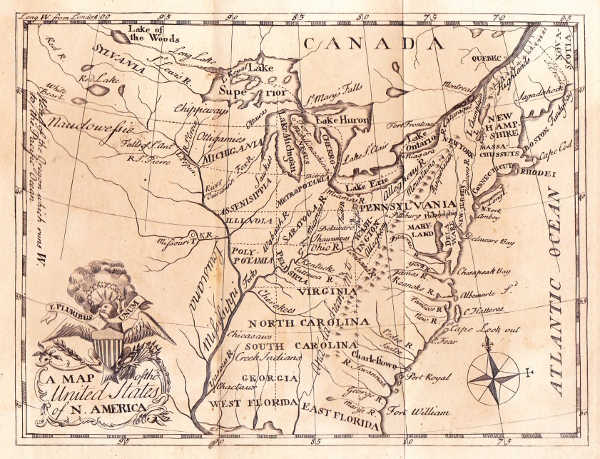

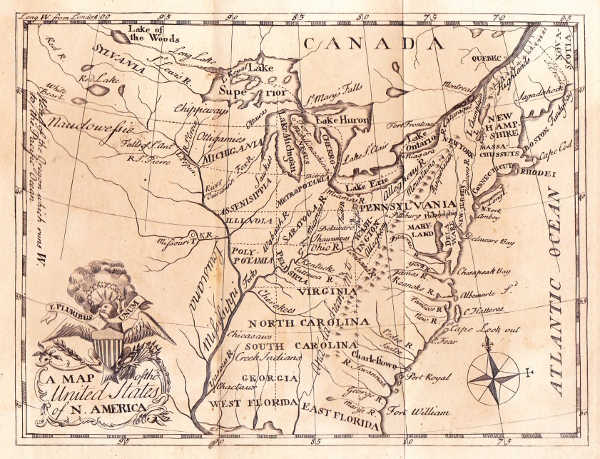

Behind this somewhat comical story lies a deeper and more important episode in American history. On this day in 1784, Congress enacted the Land Ordinance of 1784, a proposal drafted by Jefferson to divide the new land west of the Appalachian Mountains into 10 states.

Having just won their independence from Great Britain, the Americans found themselves with a mess of land that stretched deep into the continent (how deep, they did not yet know since Lewis and Clark’s expedition across this vast expanse was still two decades off).

Jefferson was a delegate of the state of Virginia and had fought for the past four years over the question of what to do with the land west of the original colonies. This was a major issue, with seven of the 13 colonies already claiming ownership of land west of the Appalachians (sometimes with overlapping borders).

In 1781 Virginia ceded its claim to the vast territory northwest of the Ohio River to the federal government, a move that ultimately made Maryland agree to sign the “Articles of Confederation” that year.

Now, after peace with Britain had finally been achieved, Jefferson was once more called on to take his pen and write up a document that people could stand behind.

This time, rather than a declaration of independence, he was to create an ordinance that would pave the way for new states to be created.

Jefferson and his proponents laid out a plan that, among other things, stated that none of the former 13 colonies should themselves create colonies of this land now or in the future but, rather, allow new areas to be divided for the creation of potential states.

This ordinance, and the ones that succeeded it, laid the foundation for the creation of additional states, each one distinct from the others.

As part of the ordinance, Jefferson also lent his considerable creativity to how the land ought to be divided and named.

Being as he was educated in the myths and history of ancient Greece and Rome, Jefferson proposed the new states of Metropotamia, Polypotamia, Sylvania, Chersonesus and six more besides.

Before you scoff, we should remember that the founding fathers were deeply affected by the ancient world, looking to the Roman Republic and the democracy of Athens as exemplars for their own budding state.

George Washington himself fashioned his public persona from the Roman figure of Cincinnatus (later the inspiration for the city of Cincinnati).

Cincinnatus was a man who rose to the highest level of power in the Roman Republic, saved the city of Rome from invading armies and spurned the position of dictator-for-life that he feasibly could have taken in favor of a quiet life back on his farm.

Sound familiar? It should, because there was as yet no term limits for a president and Washington could have feasibly continued in that high office to the rest of his days, but instead took his cue from that Roman hero and after two terms left office.

So, when Jefferson, in all seriousness, looked to the ancient past as inspiration for the new states, not everyone immediately shouted him down.

In the end Congress thanked Jefferson for the ordinance, and the idea of dividing the states, but turned down most of the proposed names. Eventually, however, some of the names did end up on America’s maps, but none of them were classically inspired.

I suppose we were not destined to have the great state of Metropotamia. The people of Wisconsin can let out a collective sigh of relief!

Antone Pierucci is the former curator of the Lake County Museum and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.