LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – The University of California Regents are denying allegations that the University of California, San Francisco Medical Center failed to take precautions against a deadly bacteria and that a Lake County child died of legionnaire's disease as a result.

On Nov. 22, the University of California Regents formally responded to the lawsuit filed in late October by Hidden Valley Lake residents Rodd and Kellie Joseph, denying any wrongdoing on the part of the UCSF Medical Center.

The couple's 7-and-a-half-month-old son, Ryland, died of legionnaire's disease, a severe form of pneumonia, at UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital on May 16, more than two weeks after he had undergone a successful bone marrow transplant to cure a rare disease, Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome.

After a doctor informed the Josephs that their son's engraftment surgery had been successful, the child abruptly took a turn for the worse, going into organ failure and dying days later.

The Josephs allege in their wrongful death suit that the hospital knew that the bacteria causing legionnaire's disease was in its plumbing system, and that the same diseases had killed two other boys who had been treated at the hospital in 1992 and 1998.

The hospital's response to the suit states that it “exercised reasonable diligence at all times,” suggests that the child's death was the result of the negligence of others, and that the hospital is immune because the child's death resulted from “the exercise of discretion vested in its employees.”

The suit response states that the child's death was “the natural course” of his condition or “the natural or expected” result of reasonable treatment rendered for his disease, and so the Josephs' claims are barred by California Civil Code.

The regents also claim immunity under Business and Professions Code sections 364 and 365, which require 90 days' notice before a legal action is taken, and the Fair Responsibility Act of 1986, which helps protect local governments in tort claims.

In a statement released to Lake County News, Josh Adler, MD, chief medical officer of UCSF Medical Center and UCSF Benioff Children’s Hospital, said the hospital learned on July 12 that the cause of Ryland's death was a form of pneumonia caused by legionella bacteria.

“We have expressed our sincerest condolences to this baby’s family. They have experienced a terrible loss,” Adler said.

“Patient safety is at the heart of what we do, and we take infections like this extremely seriously,” Adler continued. “In the ensuing months, our goal has been to understand what caused the illness in this child. Communication with the family has been a priority, and we updated them weekly throughout the investigations.”

However, the Josephs said hospital officials stopped talking to them in August, and their attempts to get answers from the agencies involved in the investigation also met with resistance and dead ends.

The Josephs have hired Baltimore-based attorney Steven Heisler, who specializes in legionnaire's litigation, who in turn brought on attorney Kevin Elder of the Bay Area firm Penney and Associates.

“I think our bottom line is, we don’t want this to happen to anyone else’s child,” said Heisler.

Elder emphasized that the suit does not claim medical malpractice, with the family believing that the doctors who treated their son did a great job.

“I am just hoping we get answers,” said Kellie Joseph. “We didn't do anything wrong, that's what we know.”

“Our biggest concern now is making the public aware that there is a deadly bacteria that lurks inside of this hospital,” said Heisler.

Added Elder, “Nobody should have to go through this.”

Seeking a cure

In February, the Josephs found out that their then-4-month-old son had Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome, a rare disease affecting mostly boys, making them susceptible to deadly conditions including autoimmune deficiencies, leukemia and lymphoma. Children with the condition usually don't live past the age of 8.

The couple studied the condition and connected with other parents and support groups. They also joined Facebook and made the search for their son's cure a public journey that was shared by people around Lake County and beyond.

In April, it was determined that the Josephs' nearly 2-year-old daughter, Brooklynn, was a match, and would donate marrow to her baby brother.

The Josephs said they would have taken their son anywhere in the world for the surgery, but they chose UCSF Medical Center because of its excellent record in successful bone marrow transplant surgeries. Rodd Joseph said the hospital is a pioneer in dealing with Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome. The fact that the hospital was only two hours from their Lake County home was another huge benefit.

Ryland went into the hospital on April 17, and subsequently underwent 12 days of chemotherapy in preparation for the May 1 bone marrow transplant surgery.

Before the baby went into the hospital, the Josephs were given a complicated set of rules to follow in order to access the hospital floor where their son would be treated. A medical screener would check them before letting them on the floor, their clothes had to be heated in a special process and repeated hand-washing was instructed.

However, the Josephs were told they could not use the shower in their son's hospital room; they recalled a hospital staffer telling them the shower contained “a bug.”

“They alluded to the fact that there is something in the water lines,” Rodd Joseph added.

The couple didn't press hospital staff on that issue. “I trusted them,” said Rodd Joseph, adding he would have asked for a different room or gone to a different hospital if he had any idea that legionella was present.

Rodd Joseph remembered a doctor coming in to tell him on May 10 that Ryland was engrafting faster than any patient he had ever seen.

“You're going to be out of here sooner than later,” he remembered the doctor saying.

But that prediction came true in a way that none of them had contemplated.

Within the next few days, Ryland began to quickly decline. He suffered high fevers and his oxygen saturation levels dropped. On May 14, he was moved into the hospital's pediatric intensive care unit. He went into organ failure and died on May 16.

Ryland's original death certificate would give the cause of death as “probable fungal sepsis.”

“They didn't know what it was,” said Rodd Joseph.

However, that conclusion would change as a result of the autopsy that the couple agreed to on the day their son died.

Both of the Josephs are law enforcement officers – Rodd is a sergeant with the Clearlake Police Department, Kellie is a detective with the Lake County Sheriff's Office – and so for them approving the autopsy was a “no brainer,” according to Rodd Joseph.

“We’re so thankful that we made that decision,” he said.

The results of the autopsy – which the couple received in the middle of July, two months after their son's death – concluded that he had died of legionnaire's disease, an ailment that is particularly dangerous for children, the elderly and those who are immunosuppressed.

In Ryland's case, he ticked two of those three boxes. Despite the successful bone marrow transplant, his immune system hadn't yet fully recovered from the chemotherapy, his father explained.

The Josephs didn't exactly know what to do with the information about Ryland's cause of death, but one action they took was to get Ryland's death certificate modified. Eventually it was changed to list the cause of death as legionella pneumophila pneumonia.

In thinking back on the situation, Kellie Joseph said she's disturbed that not only did their son become ill, but their daughter had been in the hospital to give bone marrow and so also was potentially exposed to the disease.

Rodd Joseph said he was angered to find out that the room where Ryland had been staying was reopened to other patients a short time after his death, before the cause of his death had been identified.

With the exception of time he had a central line implanted and when he was taken out of the room to go to the pediatric intensive care ward, Ryland spent almost a month in his room at UCSF Medical Center.

Legionnaire's has a two- to 14-day incubation period once exposed, according to the Centers for Disease Control. Thus, his parents and their attorneys allege that he had to have contracted it at the hospital.

Heisler said the child didn't have the bacteria when he arrived. “There's no way he could have gotten it anywhere else.”

The Josephs are puzzled about how he did get it, as they said they followed the hospital's instructions precisely and never used the room's shower.

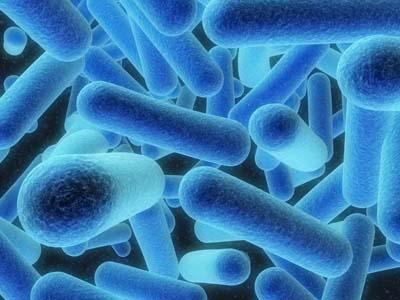

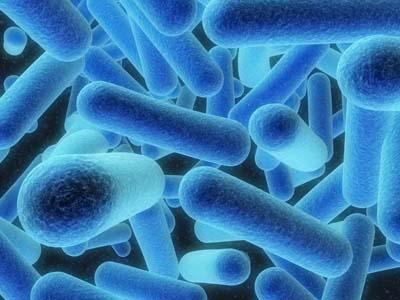

Explaining legionnaire's disease

Since Ryland's death, his grieving parents have searched for answers, and have educated themselves about legionnaire's with the same vigor that they researched Wiskott-Aldrich Syndrome.

Legionella, the bacterium that causes legionnaire's disease and related conditions like Pontiac fever, is naturally occurring in the environment, particularly water. A CDC fact sheet said the bacteria grows best in warm water environments like hot tubs, hot water tanks, cooling towers and large plumbing systems.

The US Department of Labor's Office Occupational Safety and Health Administration reported that there are 43 legionella species, of which 20 are linked to human diseases.

People contract legionnaire's disease by inhaling water that contains the bacteria, according to the CDC. It is not spread from person to person.

The first documented outbreak of legionnaire's – which gave the condition its name – occurred in 1976 at an American Legion convention in Philadelphia, according to the CDC.

Since then, outbreaks have taken place at hospitals, retirement homes and nursing facilities, hotels, resorts and, earlier this fall, even a brand new Santa Clara County crime lab. However, health officials say most cases are isolated and involve single patients.

Most people exposed to the bacteria don't become ill – only an estimated 5 percent of those exposed contract legionnaire's, according to OSHA.

The CDC estimates that every year in the United States there are between 8,000 and 18,000 people hospitalized with legionnaire's disease, of which only about 3,000 cases are reported to the CDC, which suggests the occurrence could be higher.

At the same time, OSHA reported that there are an estimated 25,000 cases of the illness nationwide each year, with more than 4,000 deaths resulting. That 15-percent fatality rate is said to be similar to other forms of pneumonia.

Health officials say legionnaire's disease is treatable with antibiotics.

According to California Department of Public Health surveillance records, legionella cases quadrupled between 2000 and 2010, rising from 57 to 222 cases statewide.

However, Lake County Public Health Officer Karen Tait questions if those numbers truly represent an increase in cases, or if they are more a result of increased reporting and more awareness of the disease.

“I think some of it is probably that,” she said of increased awareness.

Cora Hoover, MD, director of communicable disease control and prevention in the San Francisco Department of Public Health Population Health Division, was involved in the inquiry into the child's death. She said it's “entirely possible” that increased awareness and monitoring helps account for more cases.

However, she said she wouldn't speculate on the trend's ultimate cause. “I think the reasons for that increase aren't known,” she said. “You really need a long period of years to be confident that you're seeing a trend.”

Agencies investigate

Adler said that when the hospital learned the cause of the child's death, it immediately initiated an investigation, which included alerting the San Francisco Department of Public Health and the California Department of Public Health. The hospital also consulted with CDC in the investigation.

Tait confirmed that she also was “in the loop on the investigation” into that legionella case, and was included in conference calls that involved a variety of agencies taking part in the inquiry, adding there was a “tremendous effort” to investigate the case.

Because of privacy rules, she could neither confirm nor deny Ryland's individual legionnaire's diagnosis. However, she did say that the county had a confirmed case of legionella this year in a resident.

Because Tait and her office weren't directly involved in the investigation, she did not offer further comment on the case's particulars.

The CDC also was involved, but the agency said it was not in a lead role.

“The CDC’s involvement was limited,” CDC spokesperson Darlene Foote told Lake County News in an email.

Other agencies “led, and we assisted with lab support,” she said, referring Lake County News to state and local health departments for additional information.

Hoover told Lake County News that public health departments like the San Francisco Department of Public Health, by law, receive reports of communicable disease.

There is a standard list of those diseases that have to be reported. “Legionella is one of them,” she said.

Depending on what the agency thinks is the public health significance of the case, they do more or less intensive followup. In this case, Hoover said a team approach was taken due to it originally being reported as a “hospital-related” infection, which she was careful to qualify does not imply its ultimate cause or origin.

San Francisco Department of Public Health's role in the case was not that of investigator, with Hoover explaining that UCSF Medical Center conducted the investigation; rather, the agency's role was collaboration, advice and consultation. The department's involvement in the case has since concluded.

She said UCSF Medical Center followed the appropriate process by notifying her agency of the infection. There were conference calls on the case that involved San Francisco Department of Public Health officials, UCSF Medical Center, CDC and the California Department of Public Health.

Hoover said the hospital also was transparent with public health officials. “If there hadn't been such robust cooperation, that might have been an issue” with regard to the level of the agency's involvement.

As to whether the legionnaire's case was contracted at the hospital, Hoover said that information was beyond what she could share, and that it involved privacy issues about the patient's case. She added that, based on all of the agencies that came together, the conclusion about the infection's origin shouldn't be assumed.

She said San Francisco Department of Public Health worked with UCSF Medical Center on enhanced surveillance, although she didn't have the details of the measures the hospital is taking. The hospital also did not respond to Lake County News' request for information on any new prevention measures it has taken in the last six months.

Hoover cautioned against drawing conclusions that the infection was hospital-related based on UCSF Medical Center agreeing to enhanced surveillance. “No matter the conclusion, it's still a very appropriate next step.”

Lake County News asked Hoover if the hospital had previous legionella cases. She said it was her department's understanding that it had more more than 15 years since there had last been a legionella case at UCSF Medical Center. As such, health officials did not consider there to be a pattern.

This case also didn't rise to the level of an outbreak, she said, which would have required a whole other level of response.

“Really, the focus was how can we keep this from ever happening again,” she said.

When asked if there was a conclusion about how to prevent future cases, Hoover said she had trouble answering that and didn't have details about any changes that have been made to the hospital's procedures.

“We feel they responded appropriately,” she said.

Lake County News also contacted the California Department of Public Health regarding the investigation.

Spokesman Corey Egel confirmed that the agency initiated an investigation into the child's death on Aug. 27. The state investigation is now closed and the findings were released to the hospital on Nov. 14. Egel said there were no deficiencies issued against the hospital.

A copy of the one-page report, released to Lake County News, stated that the inspection was limited to the specific incident “and does not represent the findings of a full inspection of the facility.”

The California Department of Public Health had three officials – a health facilities evaluator nurse, medical consultant and an infection control consultant – involved, and “was unable to substantiate a violation of Federal or State regulations,” the document said.

When the California Department of Public Health receives a report from a facility pursuant to Health and Safety Code Section 1279.1 referring to adverse events, or a written or oral complaint involving a licensed health facility that indicates an ongoing threat of imminent danger of death or serious bodily harm, it conducts an investigation of the reports and/or complaints, Egel said.

He said the agency also investigates cases of reportable diseases or unusual occurrence reports that threaten the welfare, safety or health of patients, personnel or visitors.

In Ryland Joseph's case, the California Department of Public Health's Licensing and Certification program’s investigation did not include conducting bacterial testing in water and plumbing systems at the hospital, Egel said.

Instead, he said UCSF “provided information during the investigation that the hospital contracted with an outside consultant to examine the water and plumbing systems,” and he referred Lake County News to the hospital to seek the testing results.

The hospital did not respond to Lake County News' questions about the testing results, and Elder said the Josephs asked UCSF Medical Center to voluntarily provide their testing information, but they didn't. “They're not willing to play friendly,” he said.

Egel said the California Department of Public Health Licensing and Certification program does not have any record of any previous reports of Legionnaires’ disease at UCSF Medical Center until the Ryland Joseph case, which was reported in July.

However, a 1992 Los Angeles Times story reported that a child being treated for a brain tumor at the hospital died of legionnaire's disease, with legionella detected in the sinks of both rooms where the boy stayed.

Heisler maintains that the 1992 case was a confirmed case of legionella – it's referenced in the lawsuit – and he believes it occurred on the same floor where Ryland stayed. He and the Josephs also have information that there was another legionella case in the same room in 1998.

“There's a history there of people getting legionnaire's,” Heisler he said. However, the hospital has refused to let the Josephs or their attorneys come in to test for the bacteria.

The state and county worked with CDC on the report into the case, a copy of which still hasn't been given to the family and their attorneys, said Elder.

California Department of Public Health spokesman Ronald Owens told Lake County News that the agency's Licensing and Certification program is responsible for communicating the outcomes of the investigation at the licensed facilities to the complainant and licensee.

“Only if the family member filed the complaint, then they would receive the outcome of the investigation,” Owens said.

Solutions and next steps

According to Adler's statement, “No other hospital-acquired cases of Legionella infections have been identified at UCSF or in San Francisco in the past two years. All deaths at our hospitals over the past 16 months in severely immunocompromised pediatric and adult patients were reviewed, and none were identified as the result of Legionella infections.”

He said numerous water samples throughout the hospitals were tested and the results did not show evidence of legionella in the water supply.

“Legionella bacteria are found in all man-made water systems. The City and County of San Francisco, like most municipalities, treats water with monochloramine,” said Adler.

The hospital did not respond to Lake County News' request for clarification on Adler's statement in relation to whether the plumbing system – not just the water supply – had been tested.

The recently filed lawsuit, however, states, “defendant asserts that it had a reasonable inspection system of the building water system and accordingly exercised reasonable care in maintaining and operating said system.”

Heisler, however, questioned how Ryland came down with legionnaire's if the hospital had effective prevention measures in place.

Adler said UCSF Medical Center takes further steps to mitigate exposure, consistent with industry best practices. It has a dual approach, which includes continuously heating water to 140 degrees Fahrenheit and simultaneously monitoring the monochloramine levels in city water at the entry point to the UCSF campus.

“UCSF continues to use those practices, and is committed to implementing any additional preventive measures as appropriate to protect our patients and staff,” Adler said.

Both Heisler and Elder question the effectiveness of the practices the hospital said it is using.

Chlorinating, they said, is a method that doesn't always work. Copper-silver ionization, a disinfectant process which costs $100,000 in a large system like the hospital's, is a cutting edge way to treat water and the system, and it works.

“This is preventable,” said Elder.

Heisler said the goal of the case doesn't include seeking a particular monetary amount. “How do you put a value on the life of a 7-and-a-half-month-old child?”

As for the case's status, “We’re just starting,” said Elder, noting that it could take two years to get to trial due to the backlog in the San Francisco courts.

San Francisco County Superior Court records show that a March 26 case management conference has been scheduled in the case.

Email Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. . Follow her on Twitter, @ERLarson, or Lake County News, @LakeCoNews.