LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – Once upon a time in Lake County we had a myriad of mines – gold, silver and, most of all, quicksilver, also known as, mercury mines.

Lake County borders what are now Napa, Sonoma, Colusa, Mendocino, Yolo and Glenn counties.

In the south county, in the Middletown region is where much of the mining action occurred in the 1800s.

As you are driving out of town toward Mount St. Helena, note the names of the street signs, as many denote names of mines of times past.

Some of the more prominent mines were the Bradford, Great Western, Ida Clayton, Oat Hill, Mirabel and Yellowjacket.

As per my student's book written for the California State Sesquicentennial along with former Coyote Valley Elementary School teacher, Joyce Anderson's class in 1999, which now resides in the State Archives, Sacramento, “The Mirabel Mine was the fourth largest of all of the quicksilver (mercury) mines. The last time it operated was in 1945. They got real silver from this mine, too. The Bradfords used to own the Mirabel Mine, then in the 1890s they sold it to three men: Mills, Randol and Bell. They got the name 'Mirabel' from the first parts of all of their names – Mirabel.”

The Great Western Mine in south Lake County was written about extensively in the 1950s by Helen Rocca Goss. She was the daughter of the mine's owner, Andrew Rocca.

According to Ms. Goss, her father, Andrew Rocca was the superintendent of the Great Western Mine from Sept. 12, 1876, to May 1, 1900.

In the foreword of one of her books, entitled, “The Life and Death of a Quicksilver Mine,” Helen Rocca Goss states, “For many years it has seemed to me that the long and interesting life my father led in the gold and quicksilver mines of California deserved to be recorded as a modest contribution to the state's history. To that end I began as long ago as the middle of 1930s to collect the necessary facts about his life and the milieu in which he lived by researching contemporary newspapers, mining reports, county archives – such as the assessment rolls, the recorded deeds, the court records, etc. I also talked with many people who had known Andrew Rocca, and most important of all, I asked my older sisters and brothers to write down for me their own memories of the events they themselves had witnessed or heard Father recount on numerous occasions.”

Helen Rocca Goss also relied upon her mother's diary, an invaluable wealth of information. Mary Thompson Rocca kept records in her diary from Jan. 1, 1891, to July 19, 1896.

The mine employed anywhere from 200 to 250 Chinese workers at a time, who performed the majority of the manual labor.

The Chinese laborers, known as “celestials” at the time, came from different areas of China, speaking differing dialects.

The newspapers of the time displayed blatantly bigoted monikers for the Chinese workers, such as “pigtail wearers” and “almond-eyed heathens.”

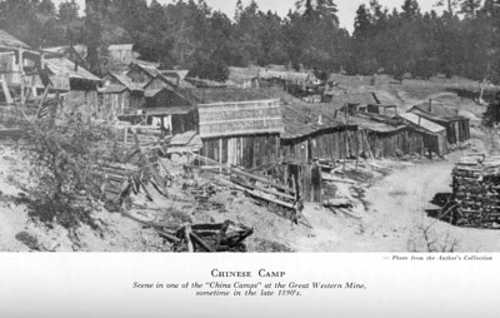

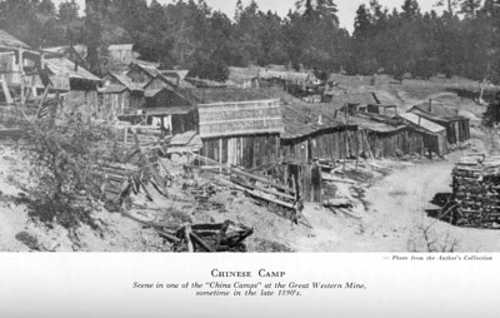

The Chinese workers at the Great Western Mine resided in two camps. The camps were basically crude huts, and sanitary conditions were not provided for.

Anything that was salvaged, such as used shingles, boxes, bits of lumber or hammered-out kerosene cans, were fashioned into huts.

Each year in the Chinese camps – sometime in late January to the third week in February – one of the grandest events of the year would occur: the celebrations of the Chinese New Year.

Then, the Andrew Rocca family, and many other non-Chinese families at the mine, would be presented with loads of gifts from the Chinese workers.

They received so many celebratory gifts, that they considered the Chinese New Year as one of their own traditional holidays.

The gifts from the Chinese included poultry, nuts, candy, silk handkerchiefs, bourbon, cigars, cakes and more.

Prior to the Chinese New Year's festivities the Chinese would present gifts of Chinese sacred lily, or narcissus bulbs.

Sometimes lovely brocaded silk fabrics were given, as well as Chinese slippers, vases, fans and foods like litchi nuts, cocoanuts, ginger, tangerines and sugar cane.

A variety of firecrackers as well as a prodigious amount of fireworks would make their way into the Chinese camps at the Great Western Mine.

This was a time of celebration for not only the Chinese workers, the mine workers and their families, but numerous Middletown residents would come up to the mine for the festivities.

Helen Rocca Goss wrote, “Long strings of dozens of bunches of firecrackers were hung by their fuses from poles, topped with figures of birds and beasts full of black powder. The string was lighted at the bottom, and after all of the firecrackers had exploded with a sharp sizzle, the powder went off with a terrifying roar. Bombs full of powder were also thrown, and rockets were sent up. An entry in my mother's diary one year says that, '110,000 fire crackers and numerous bombs were exploded.' After the fireworks were over, the Chinese passed out gifts of nuts and candy to all the spectators.”

This year, in 2015, Chinese New Year is celebrated on Thursday, Feb. 19.

Chinese New Year translates as “spring festival” in China, and has been celebrated for centuries. In the past it was a celebration to honor ancestors and gods.

The Chinese calendar marks 12 months in major cycles of 60 years, with the year named for one of the 12 animals in the Chinese zodiac. The 12-year cycles repeat themselves.

This year, in 2015, it is the year of the sheep (goat). For a listing of Chinese New year animals from calendar years beginning in 1900: http://www.infoplease.com/ipa/A0002076.html .

Kathleen Scavone, M.A., is an educator, potter, writer and author of “Anderson Marsh State Historic Park: A Walking History, Prehistory, Flora, and Fauna Tour of a California State Park” and “Native Americans of Lake County.” She also writes for NASA and JPL as one of their “Solar System Ambassadors.” She was selected “Lake County Teacher of the Year, 1998-99” by the Lake County Office of Education, and chosen as one of 10 state finalists the same year by the California Department of Education.