LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – New information supplied by a death row inmate may soon lead investigators to Lake County in search of the bodies of 14 murder victims.

The latest development in the “Speed Freak Killers” case also has raised concerns that – in addition to the two men who ultimately were convicted of the horrifying series of murders – there may be two other suspects who were involved.

Wesley Shermantine, now 46, and his partner in the crimes, Loren Herzog, were dubbed the “Speed Freak Killers” because the killings they carried out – which took place over a 15-year period, ending with their arrests in 1999 – had been fueled by methamphetamine.

Since the start of this year, information Shermantine has supplied to authorities has led to the discovery of the remains of what are believed to be numerous, previously unknown victims of the pair.

Originally it was believed the men were responsible for about 15 murders, but officials now estimate the pair’s victims could number more than 70. A March San Francisco Chronicle article, quoting an inmate who claimed to have spoken to Herzog in prison, put the possible victim count as high as 112.

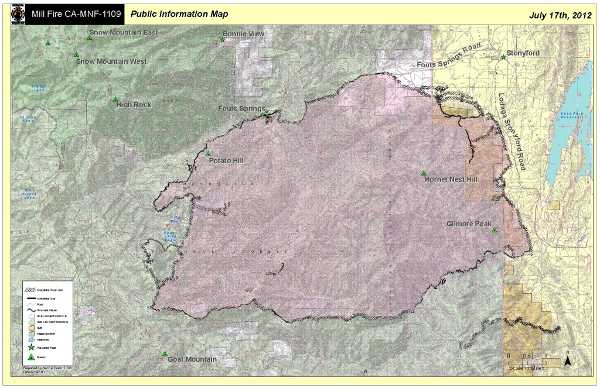

Within the last month, Shermantine revealed that the bodies of another 14 murder victims are located in Lake County’s Cow Mountain area.

Sacramento bounty hunter Leonard Padilla – who has been working with Shermantine on the release of information – said Shermantine brought up the Cow Mountain area about four weeks ago, but offered no specifics about where in that area the bodies were located.

Padilla told Lake County News that he called Sheriff Frank Rivero on Tuesday about the situation.

“I contacted the sheriff and said, ‘Hey, here’s what I got,’” Padilla said.

Sgt. Steve Brooks of the Lake County Sheriff’s Office told Lake County News that the agency had received some information about the case, but the sheriff’s office has not made any other details available so far.

New legislation aids the search

The public revelation about the possible burials on Cow Mountain came in tandem this week with Gov. Jerry Brown’s signing of AB 2357, a bill authored by Assemblymember Cathleen Galgiani (D-Stockton), whose district had been home to several of the pair’s murder victims.

Galgiani’s bill, in effect until next Jan. 1, allows for the secretary of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation to temporarily remove an inmate from prison “for the purpose of permitting the inmate to participate in or assist with the gathering of evidence relating to crimes,” according to the bill’s language.

It took effect as an urgency statute immediately upon the receiving the governor’s signature.

“It’s a lot to take in all at once,” Galgiani said of the case during an interview with Lake County News on Thursday.

She said she was working to connect with state Sen. Noreen Evans and Assemblyman Wes Chesbro – who represent Lake County in the state Legislature – as well as county leaders, in the wake of the newest revelations that bodies might be found here.

“I don’t want to have families in your area going through what we’ve been going through,” she said.

Padilla said he’s not sure what happens next, but he believed the matter is now in the hands of the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation as to whether it takes the initiative. He also suggested he could seek a court order to move forward the possibility that Shermantine is brought to Lake County.

Jeffrey Callison, press secretary for the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, said the agency had no comment on whether or not Shermantine was set to be transported to Lake County to aid the investigation.

“If it were happening it would be an investigation and we don’t comment on any ongoing investigation in that way,” Callison said.

The Ukiah office of the Bureau of Land Management oversees the Cow Mountain Recreation Area, where Shermantine and Herzog reportedly used to go hunting.

David Christy, a spokesman for the Bureau of Land Management’s Central California Unit – which includes the Ukiah office – told Lake County News that by midweek the agency hadn’t received any requests to excavate in the recreation area.

However, he said the BLM would cooperate if it did receive such a request.

The San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office – which has been the lead agency pursuing Shermantine’s information and recovering evidence of additional murder victims based on his directions – did not return a message seeking comment on Thursday.

So far, no possible identities have been offered for the victims said to be buried in Lake County – with which Shermantine and Herzog weren’t previously linked. The information offered by Shermantine so far hasn’t made clear if the victims he claims are buried there were from the county or were brought here from other areas.

Galgiani said numerous jurisdictions around the state are reassessing missing persons cases as possible homicides in light of Shermantine’s revelations.

The California Attorney General’s Missing and Unidentified Persons Unit database lists six Lake County residents.

Two of those individuals – Steven William Branston, 20, who was last seen in Lakeport in August 1996, and Robert Blair Sturgill, 30, last seen in Lucerne in 1990 – disappeared during the time frame of the murders Shermantine and Herzog committed.

However, in previous interviews with Lake County News about local missing persons cases, local law enforcement suggested Branston actually was spotted out of state at one point after he was last seen locally.

Local authorities have not yet reported if they will try to link any local missing persons cases to Shermantine and Herzog.

A destructive trail around California

Shermantine and Herzog were arrested in March 1999.

Shermantine was convicted of killing four people – Paul Cavanaugh, Howard King, Chevelle Wheeler and Cyndi Vanderheiden. He received the death penalty in May 2001 and was sent to San Quentin State Prison.

Herzog was sentenced to 78 years in to life in December of that same year for three of the murders. However, in 2004 an appeals court overturned Herzog’s conviction, finding his confession was coerced.

He later reached an agreement with prosecutors to plead to voluntary manslaughter in Vanderheiden’s death, and being an accessory in the murders of Henry Howell, King and Wheeler, besides drug charges. Altogether, he received a 14-year sentence, with credit for six years he already had served.

Herzog was paroled in 2010. He had been scheduled for release back to Galgiani’s Central Valley district.

Galgiani worked to stop Herzog’s release from High Desert State Prison in Susanville, but after exhausting all recourses to stop his parole she was able to force his release to a trailer on prison grounds.

Herzog died in January at age 46. He hung himself after Padilla informed him that Shermantine was about to release the locations of some of the additional murder victims for which they had not been tried.

Galgiani credited Padilla with helping get Shermantine to divulge the information about the additional murder victims. Early on, Shermantine was asking for money, and Padilla provided him with a reported $33,000 to cover restitution and some other expenses.

Shermantine has written Galgiani several letters. In one she received May 30, Shermantine told her that between three inmates – including himself, with the other two not being named – there were 14 victims that he could help locate, in an area where he used to hunt.

She said he didn’t specifically mention Cow Mountain in that letter. In the weeks since, however, that was the area where he told Padilla the 14 bodies would be found.

Asked if she thinks that Shermantine and Herzog had accomplices, Galgiani said yes. “I’ve always believed that.”

Padilla said Shermantine named two men – whose first names are Jason and Marcus – who were accomplices to him and Herzog.

Like Padilla, Galgiani believes Shermantine is telling the truth, pointing out that the maps he’s drawn and the letters he’s written have helped lead authorities to human remains, including 1,000 bone fragments and pieces of clothing and jewelry found in February in an abandoned well near Linden.

Galgiani said one of her constituents went to visit Shermantine in San Quentin, with the woman asking about the location of her child’s remains. “He promised her he would return her baby to her, and he did,” said Galgiani.

“No family member should have to beg to have their child back because law enforcement won’t act,” she added.

An appeal for federal assistance

Galgiani’s issues with law enforcement are particularly pointed at the Federal Bureau of Investigation. She said the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office, which had concerns over security issues, halted attempts to take Shermantine to burial sites.

The murders ultimately could involve 21 counties around California as well as communities in Nevada. Galgiani said authorities in Reno are investigating the possibility that a young woman who disappeared in 1996 was one of the pair’s victims.

Because of the multiple jurisdictions involved, in February and March Galgiani personally appealed to FBI Director Robert Mueller, asking that the FBI reopen its 1999 serial murder case on Shermantine and Herzog, and provide support from its Evidence Recovery Team in the search for victims.

“I request that the FBI, as evidenced by its history, exercise its leadership and expertise in these cases to address the continuing suffering of the victim families in Northern California. I believe it is the domain of the FBI to step in and assist, and work collaboratively with local law enforcement agencies, particularly given the complexities of this case, so that families may finally bring their loved ones home,” she wrote in the February letter.

In March, she followed up in another letter, pointing out to Mueller that Congress granted the FBI the authority to investigate serial killings upon the request of a law enforcement agency “with investigative or prosecutorial jurisdiction.”

In April, Galgiani received a letter from Jayne Challman, chief of the FBI’s Violent Criminal Threat Section.

Challman told Galgiani that a representative from the FBI’s Sacramento Field Office attended a Jan. 20 meeting at the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office, at which time it was determined that the jurisdiction remained with local law enforcement, “as no federally predicated offense exists at this time.”

Challman continued, “At the time of this letter, no change has occurred in the legal status, and the jurisdiction of the case remains with local authorities within California.”

The letter stated that the San Joaquin County Sheriff’s Office had requested support from the FBI’s Evidence Response Team, “and plans are underway to provide the proper assistance in terms of both manpower and equipment.”

Galgiani said she doesn’t believe Shermantine is going to stop trying to give information to bring the victims home.

She said family members of missing people all over the region are being left to wonder if their loved ones are among the victims.

“This is not going away,” Galgiani said. “I’m not letting it go.”

Email Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. .

022212 Assemblymember Cathleen Galgiani Letter to FBI030212 Assemblymember Cathleen Galgiani Letter to FBI