LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – For those who live along the Pacific Rim, earthquakes are part of life.

In Lake County, in recent years earthquakes have seemed to become more common, an issue attributed primarily to activities at The Geysers geothermal steamfield, the largest complex of geothermal power plants in the world, according to Calpine.

Being able to better predict the state's earthquake activity in order to help keep its residents safe is an ongoing task for seismologists, who recently completed an updated California earthquake forecast.

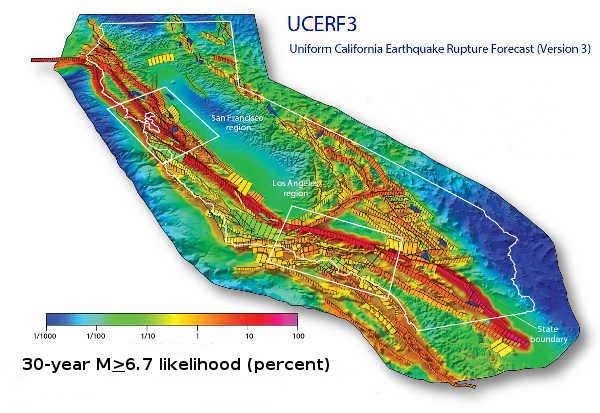

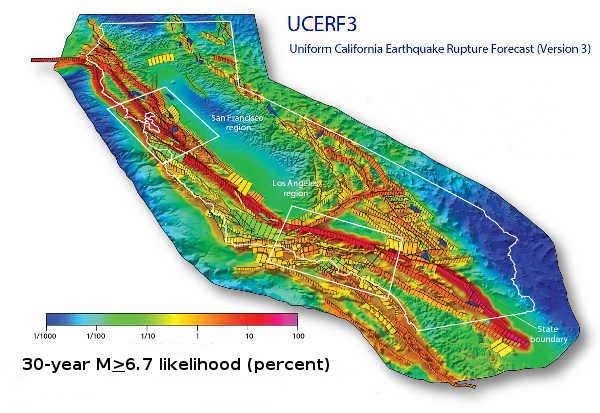

The forecast, the Third Uniform California Earthquake Rupture Forecast, or UCERF3, was released in March by the U.S. Geological Survey, which completed the work along with the Southern California Earthquake Center, the California Geological Survey and the California Earthquake Authority.

The new forecast revised scientific estimates for the chances of having large earthquakes over the next several decades, confirmed many previous findings, shed new light on how the future earthquakes will likely be distributed across the state and estimated how big those earthquakes might be, the US Geological Survey reported.

The agency said UCERF3 improved upon previous models by incorporating the latest data on the state’s complex system of active geological faults, as well as new methods for translating these data into earthquake likelihoods.

The US Geological Survey said that, when compared to the previous assessment issued in 2008, UCERF2, the estimated rate of earthquakes around magnitude 6.7 – the size of the destructive 1994 Northridge earthquake – has gone down by about 30 percent in the new forecast.

The UCERF3 forecast says the expected frequency of such events statewide has dropped from an average of one per 4.8 years to about one per 6.3 years.

At the same time, however, the new estimate is that the likelihood that California will experience a magnitude 8 or larger earthquake in the next 30 years has increased from about 4.7 percent for UCERF2 to about 7.0 percent for UCERF3.

“The new likelihoods are due to the inclusion of possible multi-fault ruptures, where earthquakes are no longer confined to separate, individual faults, but can occasionally rupture multiple faults simultaneously,” said lead author and USGS scientist Ned Field. “This is a significant advancement in terms of representing a broader range of earthquakes throughout California’s complex fault system.”

“We are fortunate that seismic activity in California has been relatively low over the past century. But we know that tectonic forces are continually tightening the springs of the San Andreas fault system, making big quakes inevitable,” said Tom Jordan, director of the Southern California Earthquake Center and a co-author of the study. “The UCERF3 model provides our leaders and the public with improved information about what to expect, so that we can better prepare.”

The Lake County picture

Concern about big earthquakes also is present in Lake County, where impacts of large quakes have been felt in the past – even when those quakes have occurred on faults that don't run through Lake County.

That was the case with the earthquake on April 18, 1906, that ravaged San Francisco. While that quake was on the San Andreas fault, which is west of Lake County, its destructive power had a definite impact on Lake County.

The quake damaged the bell tower of the Lower Lake Schoolhouse as well as many buildings – including the Lake County Courthouse – in Lakeport, and destroyed the Lakeport Masonic Lodge. For more information on that quake's local impact, see http://goo.gl/BocWtW .

Jack Boatwright of the US Geological Survey said seismologists believe that the recurrence rate of 1906-type events on the northern San Andreas fault is about once every 200 years.

“Since only 100 years has gone by, that means that it's not perceived as particularly ready to have an earthquake there,” he said.

Other major earthquakes on the San Andreas fault, including one on the north end of San Pablo bay at the end of March 1898 and another in April of that same year in Mendocino County, also were felt in Lake County, Boatwright said.

“They didn't cause any damage,” said Boatwright.

Boatwright said old newspaper accounts helped him track those events. Such accounts also help create a historical record of major events, which is critical for seismologists.

But those earthquake events are relatively recent in geological terms, Boatwright said.

Overall, seismologists only have about 250 years of really hard information, and in Northern California they're not sure how good that information really is, he said.

The best information that Boatwright said geologists have goes back to about 1776, the time of the Spanish settlement of San Francisco.

The real difficulty in California, Boatwright said, is that in order to make or to test a model of this sort of statistical depth, scientists need thousands of years of data.

“That's why when we changed the model we get these changes in the probability,” he said. Between the model that came out four years ago and this one, “we don't really have improved information in Northern California.”

Boatwright said that, for the purposes of classifying seismic regions, Lake County is located in the Coastal Northern California region, which is just slightly outside of the San Francisco region.

While the San Andreas fault doesn't run through Lake County, there are other major faults here and other seismicity issues, Boatwright said.

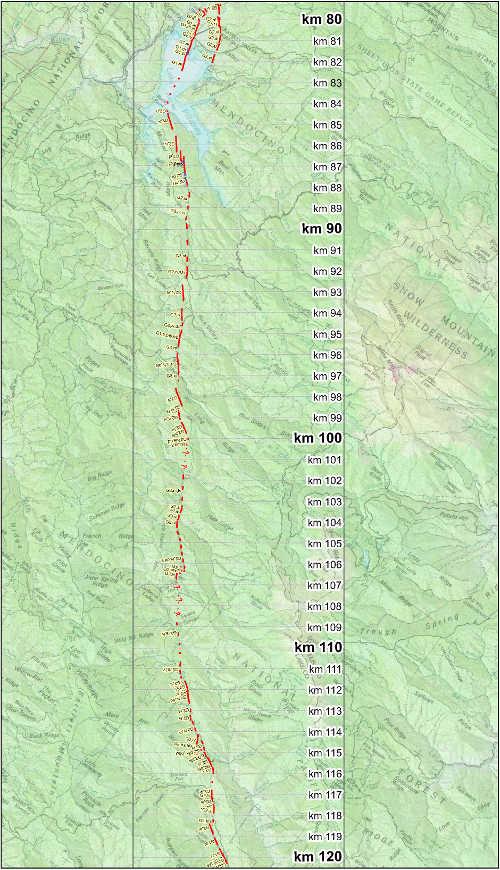

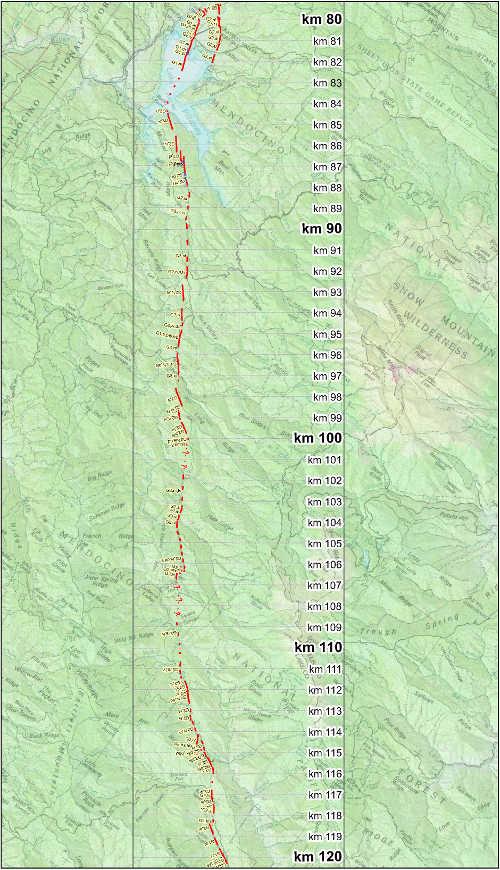

Major faults in Lake County include the Maacama, which US Geological Survey geologist Jim Lienkaemper said runs from the Russian River area, from Cloverdale to Hopland and into Lake County, as well as up to Ukiah and Willits, following Highway 101.

Then there is the extension of the Concord-Green Valley fault, a fault system which includes a subsection known as the Bartlett Springs Fault Zone. Another subsection is in the Berryessa area, Boatwright said.

The Bartlett Springs Fault Zone is associated with the larger San Andreas fault system, although the San Andreas fault itself doesn't cross into Lake County. According to the US Geological Survey the Bartlett Springs fault is estimated to be as much as 2 miles wide to roughly 100 miles long,

The Green Valley fault is basically the same at the Bartlett Springs fault, except it is in Sonoma and Napa counties, not Lake, Lienkaemper said.

US Geological Survey reports indicate that the agency mapped a large portion of the Bartlett Springs Fault Zone in the 1980s as part of a mineral resource appraisal of two U.S. Forest Service roadless areas.

“It’s not a very well studied fault,” Lienkaemper said of the Bartlett Springs fault. “That’s the big problem there.”

A lot of effort has been put into studying the Hayward and San Andreas fault, said Lienkaemper. However, the farther one gets out from the urban areas, the less study there is of faults.

The takeaway from the report is that the state's large faults – including the San Andreas, Maacama and Bartlett Springs – are more likely to host a 6.5-magnitude and above event than previous models showed, Boatwright said.

The increase in the likelihood of such larger events “is well within the uncertainty of our estimates,” Boatwright added.

While Boatwright noted, “The Geysers is very active,” he said it isn't on the Maacama fault. “It's its own little piece.”

He explained that earthquakes didn't start happening at The Geysers until water was being pumped into the area for steam injection.

“It's not a coherent, through-going fault,” he said, explaining that it's the stress underneath the ground, not a bigger fault system, that is the cause of The Geysers area's seismic activity.

Boatwright said there has been some good work done to understand the Maacama fault near Ukiah, as well as on the geodetics – or earth measurement – of the North Coast region to show how the area is progressively deforming, straining or building up strain on faults.

Overall, the Maacama fault moves, or creeps, by about 10 millimeters a year, compared to the 20 millimeters a year tracked on the San Andreas. Boatwright said the Bartlett Springs fault builds up about 6 millimeters of strain per years.

“Six millimeters a year seems like a very strong result,” said Boatwright.

When they can, geologists like to dig trenches in fault areas to so they can see what Boatwright calls “paleoseismic events” – meaning, they can find geologic records for the time before they have historical accounts for the area.

“If we're particularity lucky, we can get some material and date the events,” he said.

Lienkaemper said paleoseismic research gives scientists a look at the real history of faults, and allows them to form a long-term estimate of how frequently long-term quakes happen.

That, he said, is better than theoretical data.

Such trench work has been done in Ukiah and on the Bartlett Springs fault area, Boatwright said.

Lienkaemper worked on a mini trench on a connection between the Bartlett Springs and Green Valley faults in the summer of 2014.

It's been hard to find good trench locations in the area, and while he said he didn't find a lot of useful information in that trench, he had better success on a site on the Berryessa fault in Napa County a few years earlier, where there is a lot of seismicity.

One place where a big earthquake could occur in Lake County is the area of Newman Springs, one mile north of Bartlett Springs, Lienkaemper said.

“That is the bad place,” he said, noting it's been showing a small amount of creep.

Lienkaemper explained that the Bartlett Springs fault north of Lake Pillsbury “creeps quite a bit,” or around 6 millimeters annually.

That's good, he explained, because the creep releases the strain that would otherwise store up energy.

“The more efficient it creeps, the better it is,” Lienkaemper said.

Email Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. . Follow her on Twitter, @ERLarson, or Lake County News, @LakeCoNews.