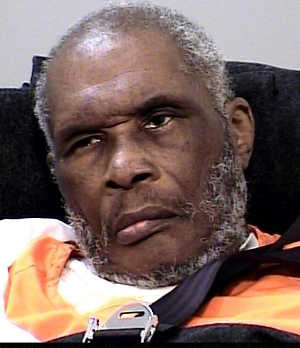

LAKEPORT, Calif. – On Tuesday morning a Lake County judge took swift action to set in motion the release of a man who has spent 18 years in state prison for a crime he did not commit.

After meeting both in chambers and in open court with District Attorney Don Anderson and attorney Angela Carter – who heads up the county's public defense contract – Judge Andrew Blum signed a writ of habeas corpus to free Luther Ed Jones Jr. from state prison.

Jones, 71, was sentenced to 27 years in prison after being convicted in 1998 of the sexual molestation of his ex-girlfriend's 10-year-old daughter.

That young girl, now a 30-year-old woman, contacted the Lake County District Attorney's Office Victim-Witness Division on Feb. 9 to admit that her mother had told her to lie in retaliation for Jones winning custody of a 2-year-old daughter he and his ex-girlfriend had together.

Anderson moved quickly to begin the process of seeking Jones' release in recent days, and partnered with Carter to bring the matter forward.

He filed the writ of habeas corpus on Tuesday, and both he and Carter said later that they had expected the process to include the setting of a hearing within 15 days, Jones' transport to the county and a local hearing before a release by the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation was finalized – which Carter estimated could have taken about a month and a half.

However, after speaking with Anderson, Senior Deputy District Attorney Ed Borg and Carter at length, going over the material, thoroughly questioning Anderson and asking him if he thought Jones was innocent, Blum surprised them by granting the writ, saying he wanted Jones released “immediately,” according to Anderson.

“He didn't want the guy to spend another day in jail that he didn't have to,” Anderson said.

There had been some question about whether Blum could hear the case, as he had worked in the District's Attorney's Office in the mid-1990s. However, Carter and Anderson said Blum addressed that issue, explaining that he had left for a job in Micronesia by the time the case was filed.

An elated Carter said Blum's action took guts.

“He cut through bureaucratic tape in about an hour,” she said.

While innocent people do go to prison, Carter said the county's elected district attorney and elected judge acted in the fastest way possible to address the matter. “It was handled exactly right.”

In her more than 20 years of practicing law in Lake County, Carter said, “I've never seen this happen before. ”

Anderson, too, noted of the exoneration, “It is so rare I've never seen one before,” adding that his office isn't usually involved in working for prisoner release actions.

Linda Starr, legal director of the Northern California Innocence Project at Santa Clara University School of Law, called Judge Blum's actions “really remarkable.”

She said it usually takes a much longer time frame for a writ of habeas corpus action, “but it's often contested as well.”

Starr also lauded Anderson for doing “the right thing” by investigating the matter and moving quickly.

“We all hope that that's the way it would work,” Starr said.

By Tuesday afternoon, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation had received the writ approved by Blum ordering Jones' release, according to spokesman Luis Patino.

At that point, Anderson didn't believe Jones had been told of the developments. “They'll break the news to him,” he said of prison officials.

Background of the case

As the matter has moved forward, it has revealed not just the injustice done to Jones, but the suffering of the young girl on whose testimony the case depended.

Anderson's writ of habeas corpus filing seeking Jones' release explained that the falsified case against Jones, which began in 1996, had its roots in his turbulent and violent relationship with the mother of his then 2-year-old daughter.

He had spent six months in jail for a domestic violence case against the woman, and after his release filed a paternity action to get custody of his young child, which was successful. On Aug. 26, 1996, the court entered a judgment giving him the child, who he took custody of two days later with the assistance of the Clearlake Police Department.

On Aug. 30, his ex-girlfriend's 10-year-old daughter reported to the principal at Lower Lake Elementary School that she had been the victim of sexual abuse.

That set in motion a Clearlake Police investigation that led to a criminal filing against Jones on Oct. 3, 1997, and his arrest 17 days later.

He went to trial in February 1998, resulting in a hung jury, with jurors deadlocking 7-5 for conviction.

At the end of March 1998, Jones' second trial – which lasted four days – began.

The young girl who he was accused of victimizing testified, as did a medical expert regarding a physical exam the girl had undergone.

Jones also testified, saying he was never home alone with the girl and that he believed she was being coached by her mother because of the case over his young daughter.

A woman named Yolanda Davis also testified for the defense regarding a conversation she had with Jones' ex-girlfriend, who said she would never let him get custody of their daughter, and that she would put him in jail to keep him from getting custody.

On April 8, 1998, the jury returned with guilty verdicts on counts of lewd and lascivious acts on a child under the age of 14, oral copulation with a minor child, harmful matter sent to seduce a minor child, forcible sexual penetration, dissuading a witness or victim, and assault and battery, according to Anderson's case history.

Jones sought a new trial, but his motion was denied and on June 12, 1998, he was sentenced to 27 years in prison.

He subsequently appealed his conviction to the First District Court of Appeals, raising issues of inadmissible evidence, abuse of discretion and insufficient evidence to sustain a conviction. The appellate court upheld the conviction.

He sought the California Supreme Court's review of the case based on ineffective assistance of counsel, a request the court denied in June 1999.

The truth revealed

Earlier this month, the young woman who had been at the center of the case when she was a child contacted authorities and said that Jones did not in fact molest her – that she had been coached to accuse him by her mother and that her mother's then-boyfriend had been the culprit for her sexual molestation, according to Anderson's report.

On Feb. 11, Borg and District Attorney Investigator Denise Hinchcliff traveled out of county to talk to the young woman, who they found credible, Anderson said.

She told them she was tired of having a “heavy heart” about Jones, who she recalled as being abusive to her mother.

After she told the school principal about the alleged molestation, she remembered being picked up by Child Protective Services and, from that point forward, spending time in numerous foster homes both in and outside of Lake County.

The young woman told District Attorney's Office staff that her mother was heavily into drugs, had six children by five fathers, and moved constantly from house to house with her children in order to live with other drug users.

On Feb. 4, she said she told her grandmother “about how she was having a hard time living with this lie,” which she had told some other family members about but was afraid to bring up to her mother. Her grandmother told her she should come forward and tell the truth, which is why she ultimately contacted the Victim-Witness Office.

The young woman said she contacted Jones' son, telling him she was afraid of his father. Jones' son supported her coming forward.

Now clean, sober and with a new baby of her own, the young woman told authorities that she felt she was ready to talk about the case. She said she has had no contact with Jones since the trial, and no one from her family or his had ever threatened her to come forward.

“She said it was just the right thing to do in her life right now,” Hinchcliff wrote in her interview report, adding that the young woman “said she feels really bad about taking 20 years of Luther's life from him and his family, and she hopes he can get out and be able to spend time with his family.”

“This woman is very brave for coming forward,” said Starr. “It's still a hard thing to come forward with that information. Good for her for doing that.”

Starr added, “She will have a better life because of it.”

Still at issue is what legal action may be taken against the man who actually molested the woman when she was a child, as well as the mother who made her lie.

Anderson said he hasn't yet looked at the question of prosecuting the alleged molester, but he cited potential concerns about the statute of limitations, the length of time since the crimes were committed and the fact that the woman has admitted to lying in court, which would make it difficult to convince a jury beyond a reasonable doubt that she wasn't lying again.

He said there's no physical evidence to go on, but said his office will consider pursuing the matter. “It would be difficult but possible,” he said.

As for the young woman's mother, who Anderson said no longer lives in Lake County, “We know which city she's in but we haven't contacted her yet.”

He said his staff will try to interview her as well as recontact some of the case's other original witnesses to evaluate the potential for charging her.

That also will be a difficult case due to the length of time that has passed. “We've got a lot more work to do before we can make a decision,” Anderson said.

State process under way

While the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation had the signed writ of habeas corpus in hand within hours of Judge Blum's decision, it was not clear when Jones would be released.

“We, by law, can have up to five days to process the release,” said Patino.

In that five-day period the agency will go through records to make sure there are no other warrants or detainers, he said.

With regard to Jones, although he did have a criminal history before his wrongful molestation conviction, warrants or detainers aren't likely to be an issue due to the length of time he's been in prison.

“We also make sure that if they have any medical conditions that they will have a continuum of care,” said Patino.

That is likely to be the most significant concern, as Jones has stated in court records that he has a variety of serious health conditions, among them diabetes, kidney problems and hepatitis C.

Anderson said that at a medical parole release hearing for Jones held in October, Jones was reported to be bedridden.

Patino said Jones is currently being housed at the California Health Care Facility in Stockton.

Noting that Jones' release due to exoneration is different than a regular parole, Patino said, “Everything will be done to help him reintegrate into society,” with the hope that he can be placed with his family.

The National Registry of Exonerations, a project of the University of Michigan Law School, tracks all known exonerations of convictions based on new evidence of innocence in the United States since 1989.

According to the registry, since that time there have been 1,740 exonerations of convictions nationwide, and in California, exonerations as of Tuesday – not counting Jones' case – totaled 158.

Of those California cases, the crime breakdown is as follows: murder/manslaughter, 70; sex crimes, 44; other, 24; robbery, 13; and drugs, seven. Sixty-one of the defendants exonerated were Caucasian, 49 were black, 43 were Hispanic and the ethnicity of the remaining five was classified as “other.”

The average number of years lost for those convicted was 8.57, with a total of 1,354 years lost in serving prison sentences, the registry showed.

While rare and remarkable, Jones' exoneration is not the only one to occur in Lake County since the National Registry of Exonerations began.

In May 1997, University of California at Berkeley students Brendan Loftus and Arvind Balu – ages 23 and 21, respectively, at the time – were charged with raping a 14-year-old girl at Konocti Harbor Resort and Spa.

The case became known as the “Vampire Rape Case” because the alleged victim said one of the men had cut her legs with a knife and licked the blood.

According to the registry's details on the case, both men were convicted in October 1997, with Loftus sentenced to five years in prison and Balu found legally incompetent and put in a state mental facility.

In July 1999, the California Court of Appeals set aside the convictions and ordered a hearing regarding evidence that had not been admitted, with a local judge upholding the convictions.

The appellate court vacated Loftus' convictions and Balu's rapid conviction in July 2000. Three months later, the Lake County District Attorney's Office dropped the charges against Loftus, and in 2006 Balu's convictions were set aside and, ultimately, the charges were dismissed.

Email Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. . Follow her on Twitter, @ERLarson, or Lake County News, @LakeCoNews.

LAKEPORT, Calif. – Come meet ballet’s best-loved princess and princes in an enchanted evening of classical favorites as Brigham Young University’s Theatre Ballet brings childhood dreams to life in its unique show, “Fairy Tales and Fantasy,” to be presented in Lakeport on Thursday, Feb. 25.

LAKEPORT, Calif. – Come meet ballet’s best-loved princess and princes in an enchanted evening of classical favorites as Brigham Young University’s Theatre Ballet brings childhood dreams to life in its unique show, “Fairy Tales and Fantasy,” to be presented in Lakeport on Thursday, Feb. 25.