- ANTONE PIERUCCI

- Posted On

This Week in History: The beginnings of the Pony Express

This week in history features the birth of an American icon, one that shows just how far we were willing to go to get the latest news in the middle of the 19th century.

April 3, 1860

In today’s fast-paced world of the New York Stock Exchange, where fortunes are made and lost in mere fractions of a second, instantaneous communication is imperative.

It is almost inconceivable to think that businesses of any kind could operate without modern conveniences: phones, computers and automobiles.

So integrated into our lives have these technologies become that we have literally built our existence around them. To do without them on a large scale is simply impossible. I dare you to approach a trader on Wall Street and tell him he can only use snail mail to communicate with his clients. That wolf of Wall Street would become a simpering sheep in a heartbeat.

And yet, as with any modern convenience, there was a time when people did fine without them. In fact, before April 3, 1860, businessmen and everyday citizens expected that the surest way to communicate with someone on the opposite coast of the country would be via steamer to the Isthmus of Panama, overland through jungles to the Pacific Ocean and once more by ship to San Francisco. The total journey would last a minimum of three weeks.

In 1859 an alternative to the sea route was established when three companies began operating overland mail routes. These arduous paths started somewhere in Missouri and went either south through Texas or centrally through Nebraska and Utah.

The overland companies were able to deliver messages in roughly the same amount of time as the steamers over the Isthmus of Panama.

However, these were new lines, going through territory sparsely populated over land that was a menace to the most veteran stagecoach driver. One breakdown along a single stretch of the route and the entire mail schedule would be backed up.

Of course, the steamer route was no less fraught with possible delays, between weather at sea and the choked confines of the Panamanian jungle.

Who knew that sending a simple letter could be such a gamble? But these were the exigencies that one had to count on to do business in pre-Civil War America.

The turning point was soon in coming. You see, the government began offering lucrative contracts for overland mail service in the late 1850s.

Those same new and somewhat unreliable overland routes were being operated by private companies with federal money (between $205,000 and $600,000 each year).

If anything could ensure speedier deliveries it was the possibility of making more money. Competition soon grew and by the dawn of 1860, other men hoped to cash in and bellied up to the federal feeding troth.

William H. Russell, Alexander Majors and William B. Waddell were old hats at the game of milking the federal cow. They first joined forces in 1854 to get the government contract to ship military supplies to western outposts.

The Mormon War of 1857 threatened these shipments and eventually led to the three men digging themselves into debt.

Looking once more to the government, the three partners found themselves in charge of an overland mail route, between St. Joseph’s Missouri and Salt Lake City, Utah.

After a failed start by Russell, who had split with the trio to create the Leavenworth and Pike’s Peak Express Company (which went under almost immediately), the reunited trio created the Central Overland California & Pike’s Peak Express Company (COC&PP) in November of 1859.

But they had not yet received the lucrative government contract. In a stunning move, Russell once more broke ranks and announced that the company would create an express service that could transport mail from Missouri to California in just 10 days. They’d call it the Pony Express.

Since it was created primarily as a marketing ploy by the COC&PP to gain the more financially-secure government contract for their standard overland service, it shouldn’t be a surprise that the Pony Express was a financial failure of sorts.

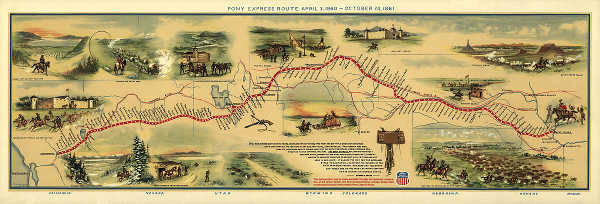

The Pony Express was designed to operate on a relay system, with a rider changing horses every 10 to 15 miles and a new rider taking over every 75 or so.

In the end, the total distance traveled along the route was approximately 1,840 miles from St. Joseph, Missouri, to Sacramento, where the mail was put on a steamer to San Francisco). Such a route required roughly 190 stations to be constructed, 400-500 horses gathered together and estimated 50 to 80 riders hired.

Announcing their intention to create the express in January of 1860, the trio set the start date for the service for April 3 of that year. They had just four months to put together these logistics. Then as now, money was a great motivator and the COC&PP got the job done.

On April 3, 1860 two riders – one in San Francisco and the other in St. Joseph – set out on the first ride of the Pony Express.

The land they crossed was unsurpassed in its ruggedness and danger, but represented the untarnished beauty of the American west. On the westward trip from Missouri the intrepid rider would race along with herds of bison numbering in the tens of thousands, dashing towards the horizon where the great expanse of the blue sky met the flowing prairie.

As with any dearly-held American story, specific details about the Pony Express are sometimes hard to verify. On the first trip, the westward-riding expressman was probably John Frye, who carried in his leather pouches about 85 pieces of mail.

Of course, he didn’t carry it the whole way and the rider who trotted into Sacramento on the afternoon of April 13 with the mail from Missouri was far removed from the riders who had hauled the load through the plains and Rocky Mountains.

Contrary to the popular myth, the company did not intentionally hire men without families to serve as their express riders. Although, they probably did look for young, lithe men eager for adventure.

Adventure they found, but only for a time. That first trip was certainly enough to light a fire in the minds of Americans. “Go west, young man,” said famed journalist of the day Horace Greely.

The Pony Express embodied that admonition and did one better: it went west faster than anyone before it. As a marketing ploy, the Pony Express worked and the COC&PP won the contract to run mail overland for the Postal Service.

In fact, it was perhaps the most effective PR campaign in American business because the memory of this great American venture still intrigues us today; this despite the fact that the Pony Express only operated for 19 months.

When the transcontinental telegraph line was finally completed in 1861, the ability to nearly instantaneously transmit information across the nation made a relic of the Pony Express.

Despite its short run, the Pony Express nevertheless persists. In memorabilia, old westerns and in the hearts and minds of nostalgic Americans, the young man on his fast horse racing towards the horizon survives.

Antone Pierucci is the former curator of the Lake County Museum and a freelance writer whose work has been featured in such magazines as Archaeology and Wild West as well as regional California newspapers.