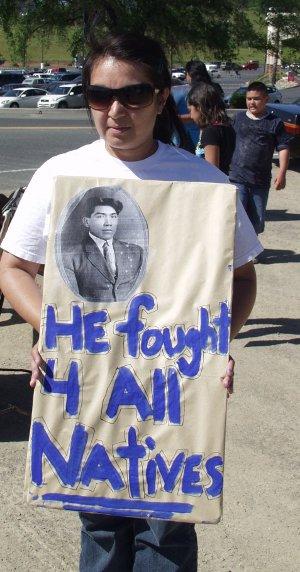

Wanda Quitiquit (foreground), along with EJ Crandell, and Irenia Quitiquit and Marion Quitiquit in the background, protested her family's disenrollment at Robinson Rancheria Resort & Casino in Nice, Calif., on Friday, May 7, 2010. Photo by Elizabeth Larson.

NICE – Throughout the day Friday, about two dozen American Indian community members and their friends stood alongside the entry into Robinson Rancheria Resort & Casino, holding signs, shouting slogans and trying to bring attention to the situation of local tribal disenrollees.

The action comes in the wake of a Bureau of Indian Affairs decision last month to uphold the December 2008 disenrollment action carried out by the Robinson Rancheria Citizens Business Council against a total of 67 tribal members, as Lake County News has reported.

Members of the Quitiquit family, several dozen of whom were disenrolled from the tribe, were back at the scene on Friday, a day they picked because it also was the fifth annual National Indian Day.

The group called for a boycott of the casino and demanded a hearing on what they argue are civil and human rights violations.

They carried signs with slogans that accused the tribe of offering the disenrollees no due process and misspending tribal and federal funding.

But the main issue was the disenrollment action, which has cut off the now-former tribal members from the rancheria and their cultural ties. They say disenrollment is an attack on their identity as American Indians.

“Why is the government backing this genocide on paper?” asked Wanda Quitiquit, one of her family's most vocal members.

A message left at the tribal office seeking comment was not returned.

Quitiquit, ironically, worked for years as a member of the American Indian Rights and Resources Organization (AIRRO), to bring attention to the growing number of disenrollment actions across California and the nation before she herself became a target of it.

AIRRO has estimated 3,500 Indians have been disenrolled in California, with a total of 11,000 civil and human rights violations across the United States as a whole.

During the Friday protest, American Indians from other tribes – including Dry Creek in Sonoma County, and the Apache and Passamaquoddy, the latter from Maine – stopped in to ask questions, as did other community members.

Natives from other areas agreed that many of the problems facing tribes is all about money.

The Quitiquits and others whose names were removed from the tribal rolls say they are planning to appeal the BIA decision, with a letter expected to go out to the agency announcing that intention this week.

“We really don't want to go into court, but if that's the last thing we have to do, that's what we'll do,” Quitiquit said.

Even a favorable court decision doesn't guarantee a welcome back into the tribe, she said, pointing to court rulings in other states that still left disenrollees without resolution.

However, there are efforts to draw attention to the disenrollment problem, both from other activists and from Lake County's congressman, who is calling for a congressional hearing on the matter.

On April 29, North Coast Congressman Mike Thompson wrote a letter to Congressman Nick Rahall, who chairs the House Committee on Natural Resources, which includes the Office of Indian Affairs.

“Disenrollment of tribal members is an issue among tribes in my district and throughout California, as well as in other parts of the United States,” Thompson wrote. “In some cases, members are voted out of tribes for bona fide reasons such as their lack of relative bloodline and/or failure to meet membership or residency requirements in accordance with tribal constitutions. However, in other cases, there appears to be arbitrary removal of entire families for obscure reasons.”

Thompson explained that when Congress passed the Indian Civil Rights Act in 1968, tribal members who believed that their civil rights were abused had no legal recourse except to turn to the tribal bodies that were accused of civil rights infringements.

“On behalf of the growing number of disenrolled Native Americans, I believe this issue merits a congressional oversight hearing be convened to review enforcement of the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968,” he said.

Late last week, Thompson's Washington, DC office told Lake County News that there had been no formal response to, or acknowledgment of, the letter yet.

Quitiquit said she and the others impacted by the disenrollment action are looking to Thompson for leadership at this time.

She credited him with being the only congressman standing up on the issue.

While the call for a hearing is welcome news to many of Lake County's disenrollees, Indian activists elsewhere are calling for more serious and systemic reform.

Laura Wass, director of the Fresno office of the American Indian Movement (AIM), is advocating for the California Indian Legacy Act.

That legislation, said Wass, “will bring everybody home and allow no more disenrollments whatsoever.”

Wass pointed out that the BIA and other governmental agencies “all love that gaming money,” which she said is a deterrent for action by some officials, who don't want to commit political suicide by going up against the tribes.

That, she said, doesn't make disenrollment a sovereignty issue, as many tribal and federal government leaders have argued.

Wass said the challenge is to get the people disenrolled from the various tribes together to work for a “full on movement,” because she believes the necessary federal changes are possible.

“It has to happen,” she said, otherwise disenrollments will continue.

“Eventually what's going to happen, I foresee, is that the tribes are going to dwindle down to families, then the feds are gonna step in,” she said.

A movement of Indians and Congress will get the necessary changes, she said.

“It's a very simple issue. You're either Indian or you're not,” she said, pointing out that Indians should qualify for membership based on blood quantum – or the percentage of Indian ancestry – and not be at the mercy of internal disputes.

Wass said that neither Secretary of the Interior Ken Salazar nor his assistant deputy and BIA head Larry EchoHawk are doing anything about disenrollment.

While she believes they're willing to do something, “They are not going to do anything until they are pushed to do it.”

Wass, who is herself a California Indian, said “California is by far the worst place” for disenrollments, which she attributed to the combination of historical trauma, the fact that rancherias are made up of several tribes and that temporary fix-it policies for tribal issues are the norm.

“We don't know what it is to have a really full, strong tribal government and still maintain cultural identity,” she said.

The internal racism is “devastating,” she said, and only continues the trauma that tribes have endured historically.

As a result, Wass said the average life span for American Indians is 47, and Indians have a teen suicide rate seven times the national average. She asked how the BIA can dare turn its back on the problem.

“Here in this state we've got a major catastrophe on our hands,” Wass said.

E-mail Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. . Follow Lake County News on Twitter at http://twitter.com/LakeCoNews and on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/pages/Lake-County-News/143156775604?ref=mf .

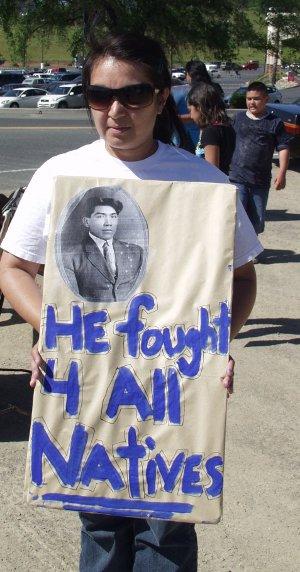

Disenrollee Tonia Ramos shows a picture of Ethan Anderson, described as a kind-hearted and generous member of Robinson Rancheria, who is an ancestor to some of the current tribal members accused of being responsible for the disenrollment action. Photo by Elizabeth Larson.