LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – Lake County’s Polar Plunge, a teeth-chattering winter foray into the murky depths of Clear Lake benefiting Lake County Special Olympics, this year will be reduced to a cooling-off period.

“This year the lake will not be as cold as usual,” said a spokesman for Clearlake Outdoors, a business on Soda Bay Road. “Usually, it’s about 50 degrees. This year it will be about 57 or 58.”

In its sixth year, the Lake County Polar Plunge is expected to attract 75 courageous water lovers to the banks of Clear Lake in Lakeside County Park, 1985 Park Drive in Kelseyville, on Saturday, Feb. 21.

About 60 of them will take the full plunge, according to Peggy Buchholz, a spokesperson for the event.

Buchholz and husband, Steve, have been involved with organizing the event for all six of the years that it's been going in Lake County, and the enthusiasm hasn't waned.

“People keep jumping in the lake,” she said.

The plunge will begin at noon with registration set to begin at 10:45 a.m. A post-plunge party will take place at 12:30 p.m. at the Kelseyville Lions Club, 4335 Sylar Lane.

Buchholz said there are about 100 Special Olympics athletes in Lake County, who the funds will assist with their sporting efforts.

“The money that we raise stays here with our athletes,” said Buchholz.

So far this year about $14,000 has been raised, said Buchholz, adding that the event averages between $12,000 and $16,000 each year.

To some of the participants, plunging a big toe will be sufficient. For that matter the tootsie plunge is brave enough for event organizers.

Those who prefer to stay out of the lake altogether will receive a hooded sweatshirt commemorating the event, just so long as they pony up $125. But they’ll be formally designated as “chickens.”

Costumes are encouraged and will be judged.

Many – if not most – participants will be members of teams. Among them is a group of lawmen including Lake County Sheriff Brian Martin calling themselves the “Shivering Sheriffs.”

Among other teams are People Services and, of course, the Chickens, who last year raised $2,125, which was only second only to a team called the Engle B.

Last year’s top 10 individual fundraisers were Tony Wymer, Beth Buchholz, Teddi Walker, Kerry Buchholz, Eric Saderlund, John Drewrey, Val Schweifler, Jordan Marquardt, Lynne Demele and B. Cheyenne.

The Polar Plunge is a nationwide event in support of Special Olympic athletes. It is the only fundraiser for Lake County Special Olympics.

For more information about the Polar Plunge, contact Steve or Peggy Buchholz at 707-279-4280 or

Donations may be sent to Lake County Special Olympics, P.O. Box 94, Lakeport, CA 95453.

General information about the Polar Plunge can be found at http://www.polarplungenorcalnv.com/faqs/ .

If you'd like to support a local team, information about teams is available at http://kelseyville.kintera.org/faf/search/searchTeam.asp?ievent=1124181&lis=1&kntae1124181=836693ED440642B6876EFD2627A0C8A4 .

Email John Lindblom at

News

- Elizabeth Larson

Cyclists vote Konocti Challenge 'Best Metric Century Ride of 2014'

LAKEPORT, Calif. – Lake County's popular fall event, the Konocti Challenge bike ride, has been voted “Best Metric Century Ride of 2014” by readers of Cycle California Magazine.

The award is announced in the magazine's February edition, a copy of which can be seen below. The announcement is on page 7.

A metric century is a ride of 100 kilometers, or 62 miles.

The Konocti Challenge is hosted annually by the Lakeport Rotary Club.

Ride Director Jennifer Strong, in announcing the award to the event's supporters, noted that it was gratifying to be honored because of the many metric centuries, as well as the fact that the awards were decided by a vote of cyclists.

The event offers challenging courses of 65 and 100 miles that wind around Clear Lake and into the foothills, a 40-mile course through the north Lakeport area and a 20-mile family fun ride.

Strong said the award comes as the Lakeport Rotary Club prepares to hold the 25th anniversary ride this Oct. 3.

Thanks to the ride's new distinction, organizers are encouraging participants to register early.

For more information about the Konocti Challenge, visit http://www.konoctichallenge.com/ and follow the ride on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/KonoctiChallengeLC?ref=stream&fref=nf .

Other bike events in honored in Cycle California Magazine included the following: double century – Davis Double; century – Tehachapi Granfondo; fun ride, Bike Around the Buttes; road race – Alta Velo Pescadero Road Race; criterium – Nevada City Classic; circuit race – Sea Otter Classic; cross country – Keyesville Classic; downhill – Sea Otter Classic; cyclocross – Sacramento Cyclocross; and endurance – 12 Hours of Temecula.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

Cycle California Magazine - February 2015 edition by LakeCoNews

- Lake County News reports

Garamendi cosponsors legislation to restore voting rights; honors Black History Month

Congressman John Garamendi (D-Fairfield, CA) has cosponsored new legislation to protect voting rights of the nation's citizens.

The two bills Garamendi cosponsored are H.R. 885, the Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2015 and H.R. 411, the SIMPLE Voting Act.

“The right to vote is the cornerstone of our democracy. The Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2015 would prevent this sacrosanct right from being abridged,” Garamendi said. “I am pleased that Democrats and Republicans have come together to introduce this legislation. I urge House Leadership to continue the strong bipartisan tradition of Voting Rights Act reauthorizations by bringing this bill to the floor without delay.

The SIMPLE Voting Act would help ensure that no American has to wait in line for several hours just to cast his or her ballot – lines that often present another type of voter suppression.

“Collectively, these bills would better safeguard our right to vote,” Garamendi said.

The bipartisan Voting Rights Amendment Act of 2015 was introduced in response to the Supreme Court’s Shelby County v. Holder decision which struck down Section 4b, the core provision in the landmark Voting Rights Act of 1965 that determines how states are covered under Section 5 of the Act (which requires federal preclearance of voting changes by covered jurisdictions to protect against discriminatory voting methods).

The bill updates the coverage formula by making all states and jurisdictions eligible for the coverage formula based on voting violations in the last 15 years.

President Lyndon Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law in August of 1965, and it has been reauthorized four times since.

President George W. Bush signed the most recent reauthorization into law in 2006, after the House voted 390-33 and the Senate 98-0 in favor of the legislation.

Key provisions in the bill include:

– Through a coverage provision based on current conditions, the bill would require states or jurisdictions that have a persistent record of recent voting rights violations over the last 15 years to abide by strong preclearance voter protection standards.

– Allows our federal courts to add the worst actors to the list of those who must abide by preclearance voter protection standards. The current law permits states or jurisdictions to be required for preclearance for intentional violations, but the new legislation amends the Act to allow states or jurisdictions to have preclearance for results-based violations.

– Greater transparency in elections so that voters are made aware of changes. The additional sunlight will deter discrimination from occurring and protect voters from discrimination.

– Allows for preliminary relief to be obtained more readily, given that voting rights cannot often be vindicated after an election is already over.

The SIMPLE Voting Act would protect the right to vote by: 1) providing for at least 15 days of early voting in every state, and 2) requiring that states provide adequate poll workers, machines and other resources to ensure that voters do not wait in line more than one hour to vote.

It also would strengthen enforcement of these rights to ensure that states comply with the bill’s provisions.

Garamendi also released a video, which can be seen above, honoring Black History Month.

- Elizabeth Larson

Purrfect Pals: A new group of cats

LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – Lake County Animal Care and Control has a new group of cats available to homes this week.

The cats – four males and two females – are all domestic short hair mixes.

In addition to spaying or neutering, cats that are adopted from Lake County Animal Care and Control are microchipped before being released to their new owner. License fees do not apply to residents of the cities of Lakeport or Clearlake.

If you're looking for a new companion, visit the shelter. There are many great pets there, hoping you'll choose them.

In addition to the animals featured here, all adoptable animals in Lake County can be seen here: http://bit.ly/Z6xHMb .

The following cats at the Lake County Animal Care and Control shelter have been cleared for adoption (other cats pictured on the animal control Web site that are not listed here are still “on hold”).

Male domestic short hair mix

This male domestic short hair mix has a black and white coat.

Hes in cat room kennel No. 8, ID No. 1755.

Domestic short hair mix

This female domestic short hair mix has an orange, gray and white coat.

She's in cat room kennel No. 43, ID No. 1745.

'Max'

“Max” is a 1-year-old male domestic short hair mix with a cool tuxedo coat.

Shelter staff said Max came in injured and his owner surrendered him.

He's a big, sweet healthy boy who is affectionate and will greet you, waiting to be petted.

Max is neutered and vaccinated, so he is ready for the right person, or family, to take him to his forever home.

He's in cat room kennel No. 53, ID 1646.

Domestic short hair mix

This female domestic short hair mix has a multi-colored coat.

She's in cat room kennel No. 55, ID No. 1737.

'Aloe'

“Aloe” is a male domestic short hair mix with a gray tabby coat.

He's in cat room kennel No. 79, ID No. 1747.

'Mokie'

“Mokie” is a male domestic short hair mix with a gray tabby coat.

He's in cat room kennel No. 98, ID No. 1746.

Adoptable cats also can be seen at http://www.co.lake.ca.us/Government/Directory/Animal_Care_And_Control/Adopt/Cats_and_Kittens.htm or at www.petfinder.com .

Please note: Cats listed at the shelter's Web page that are said to be “on hold” are not yet cleared for adoption.

To fill out an adoption application online visit http://www.co.lake.ca.us/Government/Directory/Animal_Care_And_Control/Adopt/Dog___Cat_Adoption_Application.htm .

Lake County Animal Care and Control is located at 4949 Helbush in Lakeport, next to the Hill Road Correctional Facility.

Office hours are Monday through Friday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., Saturday. The shelter is open from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday and on Saturday from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Visit the shelter online at http://www.co.lake.ca.us/Government/Directory/Animal_Care_And_Control.htm .

For more information call Lake County Animal Care and Control at 707-263-0278.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

- Lake County News reports

Yuba College to host Black History Month event Feb. 19

CLEARLAKE, Calif. – Yuba College Clear Lake Campus Human Services Student Association is presenting an event on Thursday, Feb. 19, in honor of Black History Month.

The students are inviting the public to the event which they are calling, “Black History, No Mystery.”

This free cultural and historical presentation will begin at 1 p.m. in room 209.

An opening prayer will be shared by Thomas Brown, tribal administrator and cultural director for Elem Indian Colony.

NAACP President Rick Mayo will deliver remarks. Music will be provided by professors Doug and Sissa Harris with accompaniment from their friend Bill Bordisso.

A black history poem will be shared by Delores Davis. A black history speech will be spoken by elder community member Denise Johnson.

Randall Cole will conclude with a motivational speech. Cole is the communications director of the Human Services Club, the student organizer for this event and a local author.

The event includes the option of a buffet lunch available for purchase from Aromas Café.

The buffet is available from 11:30 a.m. to 1 p.m.

The college's culinary students are collaborating by presenting a buffet lunch which features Southern Soul Food for $9 per person.

The menu includes pulled pork, Mary's free range fried chicken, wild style pulled pork pizza, collard greens, red beans and rice, full fresh salad bar, corn bread muffins, honey butter, sweet potato pie and buttermilk pie.

For questions about this event call Yuba college Clear Lake Campus at 707-995-7914.

- Elizabeth Larson

Body of missing Hidden Valley Lake man found

MIDDLETOWN, Calif. – Searchers on Sunday located the body of a Hidden Valley Lake man who was last seen by family the previous morning.

The body of 58-year-old Mark Albee was discovered at around 9 a.m., according to Sheriff Brian Martin.

Albee's family had reported him missing early Saturday afternoon. He'd last been seen at around 8:30 a.m. Saturday, according to his daughter, Michelle Smith.

Albee's Ford Ranger pickup later was found near a creek in a dirt turnout at the bottom of the Coyote Grade near Middletown, Martin said.

The Lake County Sheriff's Office and Lake County Search and Rescue began a search early Saturday evening, continuing until into the night. Martin said a helicopter also had been brought from Napa County to assist.

At 7 a.m. Sunday the search had resumed, Martin said.

Martin said Albee's body was found about 500 yards from where his pickup had been located the previous day.

“The body was recovered by one of the Search and Rescue dogs,” he said.

There are no signs of foul play, Martin said.

The cause of death is pending an autopsy, although early indications are that Albee may have taken his own life, according to Martin.

Albee's daughter said he had health issues and had been depressed, and Martin said Albee's wife had reported to authorities that he had sent her a “concerning message” around the time of his disappearance.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

- Elizabeth Larson

Motorcyclist killed in Saturday afternoon crash

MIDDLETOWN, Calif. – A Hidden Valley Lake man died Saturday afternoon when his motorcycle collided with a vehicle on Highway 175.

The California Highway Patrol did not release the name of the 51-year-old man late Saturday pending notification of next of kin.

The CHP report said the crash occurred just after 4:30 p.m. on Highway 175 west of Socrates Mine Road near Middletown.

A 62-year-old Cobb man – whose name also wasn't released by the CHP – was driving a 2002 Chrysler Sebring eastbound on Highway 175 at approximately 25 to 30 miles per hour, while the motorcyclist, riding a 1998 Honda Super Hawk, was headed westbound at an undetermined rate of speed, the CHP said.

As the motorcycle entered a turn to the right in the roadway, the rider lost control and the bike began to slide on its side, according to the CHP.

The CHP said the motorcycle continued sliding out of control on its side, crossing the highway's double-yellow lines and heading toward the Chrysler.

The vehicle's driver saw the motorcycle coming and attempted to stop, but the motorcycle continued sliding toward the car until it collided with the front of it, the CHP said.

Firefighters arrived on scene and were unable to revive the motorcycle rider, according to the report.

Both the motorcyclist and the vehicle's driver were using their safety equipment, the CHP said. The Chrysler's driver was not injured.

CHP Officer Rob Hearn is the crash's investigating officer.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

- Kathleen Scavone

Lake County Time Capsule: The 1890 White Cap Murders

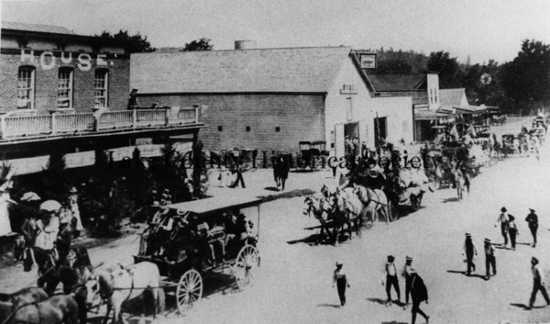

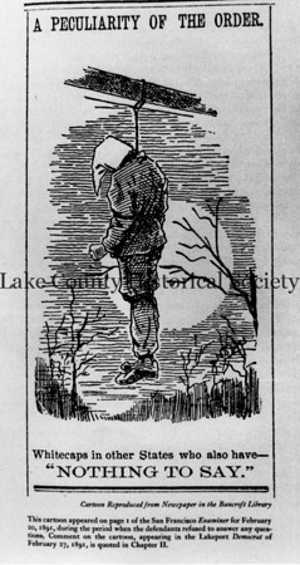

MIDDLETOWN, Calif. – The White Cap Murders that took place in Middletown, in 1890 were considered the most heinous crimes in Lake County history.

In her book, “The California White Cap Murders,” Helen Rocca Goss goes into great detail about the crimes.

White Caps were “groups of lawless bands,” according to Goss.

They formed in south Indiana, and then spread to nearby states, then finally in the West.

Goss’ father was Andrew Rocca, who was then superintendent of the Great Western Quicksilver Mine, located about three miles from the scene of the crimes.

According to Goss, he was “called to serve as a member of the coroner’s jury to examine the cause of Mrs. Riche’s death.”

But I am getting ahead of myself.

It was a typical, chilly fall Lake County evening on Oct. 10. The skies were clear and full of twinkling stars. The town was bustling with activity this particular evening, as there was a major gala social event taking place – the candidate’s ball.

About three miles south of Middletown at a saloon called “Campers’ Retreat” all was quiet.

Normally, the local quicksilver miners from the nearby mines – such as The Bradford, Mirabel, Great Western, Oat Hill or others – overflowed the establishment, drinking, playing cards and noisily debating local politics.

It was 9 p.m., and only the owner, J.W. Riche, his wife Helen Matilda Riche and Fred Bennett, the bartender, were present.

It's important to note that the name, “Riche” was spelled in varying forms by different newspapers of the day. It was spelled Ritch, Ritchie and so on, but during preliminary investigations in Middletown he spelled it, “Riche.”

While Mrs. Riche and Mr. Bennett played cards, Mr. Riche sat and observed the friendly game.

Suddenly the door was thrown open and a masked man entered the room. Soon to follow were about a half a dozen more men with shotguns, rifles and other firearms drawn.

Mr. Riche thought he recognized one of the men as a miner who worked the Bradford Mine and breathed a sigh of relief, assuming it was an early Halloween trick. When a bullet nearly grazed his head, he fully understood the serious intent of the intruders.

Mrs. Riche decided to take matters into her own hands, and promptly ripped the white cap off one of the intruders.

It seems that everything broke loose at once then, and Mr. Riche tried in vain to pull his wife to safety and shield her with his body.

Just then, a cacophony arose and a myriad of gunshots filled the room. Mrs. Riche had been wounded by a shot in her side.

Although wounded, she managed to pick up her husband’s Winchester 44 in hopes of retaliating, but her plan did not succeed.

Riche testified later that, “one man grabbed the rifle from her hand and threw it behind him.”

Then, the White Caps decided to leave the establishment. Most backed their way out, guns brazenly aimed at them, but Bennett threw the last one out.

Not to be trifled with, the White Caps opened up with a new volley of fire.

Shaken, Riche carried his wife to the bedroom and asked Bennett to go for the doctor.

While nervously awaiting the doctor’s arrival, Riche heard more footsteps on his porch.

He tore open the door and aimed his revolvers out into the dark, yelling at whoever was there that he was now quite prepared for them. It became eerily quiet.

As the festivities of the ball were beginning in Middletown, the reverie was interrupted by Bennett, who came galloping in on his horse, yelling for help.

Dr. Hartley immediately left the party, and was trailed by Constable J.W. Ransdell, Sheriff Moore, District Attorney Sayre and many others who were eager to get to the bottom of this crime.

One man, who was found by some neighbors on the Riche’s porch, could give no answers; he was dead.

It seems that it was the body of one McGuyre, who, as Dr. Hartley stated, wore “a most fiendish looking disguise.”

He was wearing an outfit with red sleeves. Burlap sacks made up the rest of his makeshift shirt and pants. White flour-sack masks were found near the house, along with a bucket of tar.

Dr. Hartley learned that Mrs. Riche had sustained five gunshot wounds. She only lived four days after the incident.

Much of the town attended services at the Middletown Methodist church, and then formed a procession to the cemetery.

The story of the murders was covered by many newspapers, including the Middletown “Independent,” the “Calistogian,” the Lakeport “Democrat” and the San Francisco “Examiner.”

Ten men were eventually arrested. Some, like Charles Osgood, chief engineer at the Bradford Mine, Charles Evans, a Bradford Mine employee, and Henry Arkarro stated that they did not intend to injure the Riches.

Instead, they had planned to attack Bennett. They wanted to “flog him well, give him a coat of tar and feathers, and then escort him to the border of the county and order him never to set foot within it again.”

Three men were turned in to the Lakeport jail without bail, accused of murder: B.F. Staley, A.E. Bichard and J. Archer, all employees of the Bradford Mine.

Before the legal proceedings were ever completed, Mr. Riche died of “apoplexy of the brain.”

It was believed that all of the sadness and stresses of the events, along with a bullet wound to his side having never healed properly, no doubt led to his early demise.

Andrew Rocca was appointed executor of his will and vowed to “champion the Riche’s cause” and “find and prosecute the perpetrators of the crime.”

It turns out that the murderers, according to historian Henry Mauldin, “were not outlaws or desperados, but just plain ordinary people, most of them were well known in Middletown or at the neighboring mines.”

At the conclusion of the trial there were no death sentences given. They spent time in San Quentin Prison, with the longest term given to a man named Blackburn, who was released on Sept. 26, 1897.

Kathleen Scavone, M.A., is an educator, potter, writer and author of “Anderson Marsh State Historic Park: A Walking History, Prehistory, Flora, and Fauna Tour of a California State Park” and “Native Americans of Lake County.” She also writes for NASA and JPL as one of their “Solar System Ambassadors.” She was selected “Lake County Teacher of the Year, 1998-99” by the Lake County Office of Education, and chosen as one of 10 state finalists the same year by the California Department of Education.

- Elizabeth Larson

Helping Paws: Ridgebacks, shepherds and terriers

LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – Lake County Animal Care and Control has a dozen dogs of varying sizes and breeds needing new homes this week.

Dogs available for adoption are mixes of cattle dog, Chihuahua, Doberman, English Bulldog, pit bull, Rhodesian Ridgeback, Shar Pei and shepherd.

Dogs that are adopted from Lake County Animal Care and Control are either neutered or spayed, microchipped and, if old enough, given a rabies shot and county license before being released to their new owner. License fees do not apply to residents of the cities of Lakeport or Clearlake.

If you're looking for a new companion, visit the shelter. There are many great pets hoping you'll choose them.

In addition to the animals featured here, all adoptable animals in Lake County can be seen here: http://bit.ly/Z6xHMb .

The following dogs at the Lake County Animal Care and Control shelter have been cleared for adoption (additional dogs on the animal control Web site not listed are still “on hold”).

Chihuahua mix

This male Chihuahua mix is 6 years old.

He weighs 5.4 pounds and will be neutered when he is adopted.

He's in kennel No. 4, ID No. 1751.

Pit bull terrier mix

This handsome male pit bull terrier mix has a short tan and white coat.

He is about 2 years old and weighs 70 pounds. He was found in the Kelseyville area as a stray.

Shelter staff said he loves people and can't wait to be in a new home.

He's in kennel No. 6, ID No. 1664.

'Baby'

“Baby” is a female pit bull terrier mix.

She has a short black and white coat.

She's in kennel No. 7, ID No. 1763.

'Copper'

“Copper” is a young male pit bull terrier mix.

He has a short red and white coat, and already has been neutered, so he has a low adoption fee.

Copper is in kennel No. 8, ID No. 1738.

Pit bull terrier mix

This female pit bull terrier mix has a pretty face and a short gray and white coat.

She's 2 years old and weighs 53 pounds.

Found as a stay, she is friendly loves to play with other dogs, male or female. Shelter staff doesn't recommend her for a home with cats, but she has no food guarding issues.

She's in kennel No. 9, ID No. 1663.

'Snoopy'

“Snoopy” is a 10-year-old male shepherd mix looking for a mellow home.

He weighs nearly 50 pounds and has a short tricolor coat.

He has a low adoption fee as he is already neutered.

Snoopy loves people, and he gets along with low energy dogs because in the past he was attacked by another dog.

If you have dogs and are interested in Snoopy, shelter staff requests that an application to be filled out and bring your dogs for a meet and greet

He's in kennel No. 12, ID No. 1650.

Shar Pei-pit bull mix

This 6-month-old male Shar Pei-pit bull mix has a short, dark-colored coat.

Shelter staff said he's very intelligent and energetic.

He gets along with both male and female dogs, and loves to play. He's not recommended for a home with cats and could use some training.

He's in kennel No. 17, ID No. 1684.

Cattle dog mix

This young male cattle dog mix has a short white coat with reddish-brown markings.

He is in kennel No. 26a, ID No. 1722.

English Bulldog mix

This female English Bulldog mix has white and brown brindle markings on a short coat.

She's in kennel No. 31, ID No. 1734.

Rhodesian Ridgeback mix

This female Rhodesian Ridgeback mix has a short brown coat and black markings.

She's in kennel No. 32a, ID No. 1757.

Rhodesian Ridgeback mix

This male Rhodesian Ridgeback mix has a short brown coat and black markings.

He's in kennel No. 32b, ID No. 1762.

'Mel'

“Mel” is a male Doberman Pinscher-Shar Pei mix.

He has a short brown and white coat.

He's in kennel No. 33a, ID No. 1718.

To fill out an adoption application online visit http://www.co.lake.ca.us/Government/Directory/Animal_Care_And_Control/Adopt/Dog___Cat_Adoption_Application.htm .

Lake County Animal Care and Control is located at 4949 Helbush in Lakeport, next to the Hill Road Correctional Facility.

Office hours are Monday through Friday, 11 a.m. to 5 p.m., and 11 a.m. to 3 p.m., Saturday. The shelter is open from 11 a.m. to 4 p.m. Monday through Friday and on Saturday from 11 a.m. to 3 p.m.

Visit the shelter online at http://www.co.lake.ca.us/Government/Directory/Animal_Care_And_Control.htm .

For more information call Lake County Animal Care and Control at 707-263-0278.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

- Lake County News reports

REGIONAL: Sonoma County Coroner's Office identifies woman found dead on beach near Jenner

NORTHERN CALIFORNIA – A woman whose body was found in the surf on a beach near Jenner on Feb. 7 has been identified.

The Sonoma County Sheriff Coroner’s Office said the woman has been identified as Janelle Patrice McGovern, 30, of Santa Rosa. Her family was located and informed of her death.

The agency last week had asked for the community's help in identifying McGovern, whose body had been found in an area known as Driftwood Beach on the north side of the mouth of the Russian River, as Lake County News has reported.

The Sonoma County Sheriff’s Office Violent Crimes Investigations Unit will conduct the preliminary investigation into the circumstances surrounding McGovern's death.

The Sonoma County Coroner Office is conducting a parallel investigation to determine the cause and manner of her death.

There is no information indicating that McGovern had been the victim of foul play or that the circumstances surrounding her death were suspicious, officials said.

- Lake County News reports

Earth News: NASA study finds carbon emissions could dramatically increase risk of U.S. megadroughts

Droughts in the U.S. Southwest and Central Plains during the last half of this century could be drier and longer than drought conditions seen in those regions in the last 1,000 years, according to a new NASA study.

The study, published Thursday in the journal Science Advances, is based on projections from several climate models, including one sponsored by NASA.

The research found continued increases in human-produced greenhouse gas emissions drives up the risk of severe droughts in these regions.

“Natural droughts like the 1930s Dust Bowl and the current drought in the Southwest have historically lasted maybe a decade or a little less,” said Ben Cook, climate scientist at NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies and the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University in New York City, and lead author of the study. “What these results are saying is we're going to get a drought similar to those events, but it is probably going to last at least 30 to 35 years.”

According to Cook, the current likelihood of a megadrought, a drought lasting more than three decades, is 12 percent.

If greenhouse gas emissions stop increasing in the mid-21st century, Cook and his colleagues project the likelihood of megadrought to reach more than 60 percent.

However, if greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase along current trajectories throughout the 21st century, there is an 80 percent likelihood of a decades-long megadrought in the Southwest and Central Plains between the years 2050 and 2099.

The scientists analyzed a drought severity index and two soil moisture data sets from 17 climate models that were run for both emissions scenarios.

The high emissions scenario projects the equivalent of an atmospheric carbon dioxide concentration of 1,370 parts per million (ppm) by 2100, while the moderate emissions scenario projects the equivalent of 650 ppm by 2100. Currently, the atmosphere contains 400 ppm of CO2.

In the Southwest, climate change would likely cause reduced rainfall and increased temperatures that will evaporate more water from the soil. In the Central Plains, drying would largely be caused by the same temperature-driven increase in evaporation.

The Fifth Assessment Report, issued by the United Nations Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) in 2013, synthesized the available scientific studies and reported that increases in evaporation over arid lands are likely throughout the 21st century. But the IPCC report had low confidence in projected changes to soil moisture, one of the main indicators of drought.

Until this study, much of the previous research included analysis of only one drought indicator and results from fewer climate models, Cook said, making this a more robust drought projection than any previously published.

“What I think really stands out in the paper is the consistency between different metrics of soil moisture and the findings across all the different climate models,” said Kevin Anchukaitis, a climate scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in Woods Hole, Massachusetts, who was not involved in the study. “It is rare to see all signs pointing so unwaveringly toward the same result, in this case a highly elevated risk of future megadroughts in the United States.”

This study also is the first to compare future drought projections directly to drought records from the last 1,000 years.

“We can't really understand the full variability and the full dynamics of drought over western North America by focusing only on the last century or so,” Cook said. “We have to go to the paleoclimate record, looking at these much longer timescales, when much more extreme and extensive drought events happened, to really come up with an appreciation for the full potential drought dynamics in the system.”

Modern measurements of drought indicators go back about 150 years. Cook and his colleagues used a well-established tree-ring database to study older droughts.

Centuries-old trees allow a look back into the distant past. Tree species like oak and bristle cone pines grow more in wet years, leaving wider rings, and vice versa for drought years.

By comparing the modern drought measurements to tree rings in the 20th century for a baseline, the tree rings can be used to establish moisture conditions over the past 1,000 years.

The scientists were interested in megadroughts that took place between 1100 and 1300 in North America. These medieval-period droughts, on a year-to-year basis, were no worse than droughts seen in the recent past. But they lasted, in some cases, 30 to 50 years.

When these past megadroughts are compared side-by-side with computer model projections of the 21st century, both the moderate and business-as-usual emissions scenarios are drier, and the risk of droughts lasting 30 years or longer increases significantly.

Connecting the past, present and future in this way shows that 21st century droughts in the region are likely to be even worse than those seen in medieval times, according to Anchukaitis.

“Those droughts had profound ramifications for societies living in North America at the time. These findings require us to think about how we would adapt if even more severe droughts lasting over a decade were to occur in our future,” Anchukaitis said.

NASA monitors Earth's vital signs from land, air and space with a fleet of satellites and ambitious airborne and ground-based observation campaigns.

NASA develops new ways to observe and study Earth's interconnected natural systems with long-term data records and computer analysis tools to better see how our planet is changing.

The agency shares this unique knowledge with the global community and works with institutions in the United States and around the world that contribute to understanding and protecting our home planet.

For more information about NASA's Earth science activities, visit www.nasa.gov/earthrightnow .

- Elizabeth Larson

Search under way for missing Hidden Valley Lake man

MIDDLETOWN, Calif. – Authorities are searching an area near Middletown for a local man whose family reported him missing Saturday afternoon.

Mark Albee, 58, of Hidden Valley Lake was last seen by family at around 8:30 a.m. Saturday, according to his daughter, Michelle Smith.

Sheriff Brian Martin said the sheriff's office received a report at about 1:30 p.m. from Albee's wife, who had gotten a “concerning message” from Albee.

“So there's some concern for his state of mind,” Martin said.

Martin said Albee's pickup was found in an area near a shallow creek on the Coyote Grade on Highway 29.

That area, Martin said, is now the focus of a search operation.

Smith described her father's pickup as a burgundy 1997 to 2000 model Ford Ranger crew cab with a matching burgundy camper shell. She said his pickup had already been returned to his home by authorities by Saturday evening.

Lake County Search and Rescue and sheriff's personnel are on scene, with Martin reporting that a helicopter has been called in from Napa County to assist with the search effort.

He said the search will continue through the night – or until Albee is found.

The California Highway Patrol reported that officials wanted traffic to slow down in the search area, located south of Hofacker Lane near mile post marker 12.87.

Smith said cones had been set out but no traffic control is in effect.

Albee has health issues and has been depressed. His daughter said he's never left home like this before.

Smith described her father as being around 5 feet 8 inches tall, weighing 130 to 150 pounds, with short brown, graying hair and a short gray beard. He has a tattoo of a lever on his right hand.

Anyone with information should call Lake County Central Dispatch at 707-263-2690.

Email Elizabeth Larson at

LCNews

Award winning journalism on the shores of Clear Lake.

|

|

|

|

|

How to resolve AdBlock issue?

How to resolve AdBlock issue?