- Elizabeth Larson

- Posted On

Elem tribal members file federal lawsuit to stop punitive disenrollment action

LAKE COUNTY, Calif. – Thirty members of the Elem Indian Colony of Pomo Indians have filed suit in federal court in response to what they say is a massive disenrollment effort by the sitting tribal council that would banish all of the residents of the 52-acre lakeside rancheria in Clearlake Oaks.

The petition for the writ of habeas corpus against the Elem Colony Executive Committee was filed in U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California-Eureka on Friday, according to a statement from the group.

The suit is alleging restraint on the plaintiffs’ liberty, and asks for a writ to prevent that restraint.

The disenrollment action the suit seeks to stop is being taken by the Elem Executive Committee, which according to the tribe's Web site includes Chairman Agustin Garcia, Secretary/Treasurer Sarah Brown Garcia, Vice Chair Stephanie Brown, and members-at-large Leora John and Nathan M. Brown II.

When Lake County News reached out to Chairman Garcia on Monday to get the executive committee's perspective, he said, “At this time, we have no comment.”

Altogether, 132 tribal members – 61 adults and 71 children – are being targeted for disenrollment, but not because of genealogy, according to Robert Geary, one of the petitioners in the case.

“Nobody questions our ancestry. Because who we are can’t be questioned – we descend from Elem Pomo ancestors and founders,” said Geary. “This is instead a feeble attempt by nonresident members of the Elem Colony to exact control over tribal monetary resources without wanting to live here, and even at the risk of terminating our entire Colony.”

Those slated for disenrollment include the last on-colony speaker of the Southeastern Pomo dialect, keepers of the colony’s two roundhouses, four Vietnam war veterans, and those who have led the colony’s efforts regarding the Superfund cleanup of Clear Lake and to regain control over Rattlesnake Island, a sacred Elem religious site.

Some of those facing separation from their tribe and the rancheria also would lose their homes, to which they hold legal title, and the rancheria would be left empty, the petitioners said.

They assert that, despite disenrollment and banishment becoming widespread – especially in California – it would be unprecedented for a tribe’s entire residency to be exiled.

Geary said the action is being carried out by tribal members who don't live on the rancheria. “Our relatives living on the outside are trying to cut the tribe off at the knees. We won’t let them.”

Over the last decade, disenrollment actions have occurred in tribes around Lake County, including Elem.

In 2007, 25 members of Elem were disenrolled based on allegations that they did not have the required lineage for membership.

The following year, in the wake of a disputed tribal election, Robinson Rancheria's tribal council began the process to disenroll close to 70 members of the Quitiquit family. The Bureau of Indian Affairs upheld the Robinson Rancheria disenrollments in April 2010, as Lake County News has reported.

In those cases, the primary justification used was lineage. In the present Elem case, however, Little Fawn Boland – the petitioners' attorney – pointed out that it's based on allegations of violating tribal law.

Disenrollment – which opponents call “cultural genocide” and “genocide on paper” – is such a serious concern for tribes across the nation that in 2015 the National Native American Bar Association adopted Resolution No. 2015-06, “Supporting Equal Protection and Due Process For Any Divestment of the American Indigenous Right of Tribal Citizenship.”

In its resolution, the association denounced “any divestment or restriction of the American indigenous right of tribal citizenship, without equal protection at law or due process of law or an effective remedy for the violation of such rights,” and declared “that it is immoral and unethical for any lawyer to advocate for or contribute to” any disenrollment where such human rights protections are not afforded.

The orders of disenrollment

Up to 61 adult Elem tribal members received orders of disenrollment, dated March 28, from the tribal council, alleging wrongful activity that, based on a May 2015 tribal ordinance – entitled “Tribal Sanctions Of Disenfranchisement, Banishment, Revenue Forfeiture, and Disenrollment and the Process for Imposing Them” – that allows them to be removed from the membership rolls, according to the case.

Boland wrote in her filing that the disenrollment order sent to the impacted tribal members “includes six pages of outlandish criminal accusations.”

She pointed out that the order does not question that the tribal members slated for disenrollment aren't properly enrolled.

While the 71 children and extended family members of those served with the March order haven't been served themselves, Boland said they would be exiled, too, if their families members were disenrolled or banished.

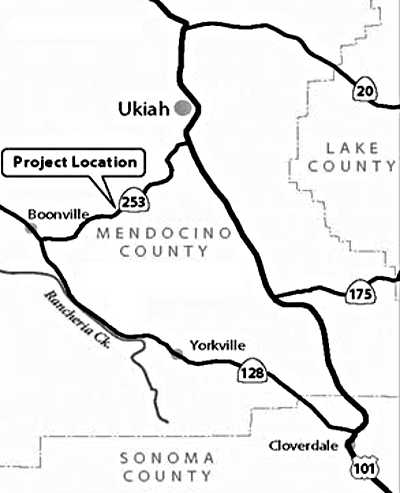

A week and a half after the date of the disenrollment orders, tribal members – along with members of the Hopland Band of Pomo Indians who had been the focus of a disenrollment action earlier this year – picketed at the Ukiah law office of Lester Marston, an attorney whose firm helped Hopland as well as Robinson Rancheria with disenrollment actions.

While the Elem Tribal Constitution requires such an ordinance to be approved by the U.S. Department of the Interior Secretary, Bureau of Indian Affairs Superintendent Troy Burdick confirmed to Boland during an April 4 email exchange that the ordinance has not been submitted for federal review and approval.

Burdick did not immediately respond to a message left by Lake County News on Monday asking if he has since received the ordinance from the Elem Executive Committee.

Separately, Boland has filed a notice of inaction appeal and motion to enforce stay with the United States Department of the Interior Board of Indian Appeals, saying that Burdick had refused to respond to her April 8 request for clarification on the validity of the May 2015 disenrollment ordinance.

The filing states that by Burdick failing to respond within the required 10 days, the matter “became ripe for appeal” to the Interior Board of Indian Appeals.

The appellants are asking that appeals board to direct Burdick to issue a decision as well as to rule that his inaction on the ordinance “also automatically stays any outcome” that resulted from his lack of action.

The roots of the dispute

For those Elem members facing disenrollment, the action the tribal council is taking against them has its trajectory rooted in a disputed election that took place on Nov. 8, 2014.

It's alleged that the sitting council – referred to as the “Garcia faction” – prevented 60 adult members from voting in that election, only allowing their supporters into the venue where the vote was held.

The 60 members who couldn't vote held their own election at a local park, electing David Brown as chairman, Adrian John as vice chairman, Paul Steward as the secretary treasurer, and Natalie Sedeno Garcia and Kiuya Brown as members-at-large.

The dispute between the two councils led to the freezing of a tribal bank account and impacts on programs, according to both sides.

Despite the efforts by David Brown and his council to be recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Burdick sent a letter to Agustin Garcia dated March 9, 2015, recognizing him as chair, along with his fellow members of the executive committee “for purposes of a government-to-government relationship.”

At that time, Sarah Garcia – who by that time had been secretary for 10 years – told Lake County News during an interview that the other tribal members who challenged the council she was a member of attempted to “pull a coup” by holding a meeting not considered legal by tribal ordinance.

She said then that it was the first challenge Elem's Executive Committee had had since a new chair was selected in 2010 following a recall.

At that time, Garcia said there were 121 people on Elem's membership roll.

The tribal members who didn't support the council recognized by the Bureau of Indian Affairs said they were subsequently treated like second-class citizens, had their rights to health care and to vote stripped, and were told they were not part of the tribe.

More recently, on the tribe's official Facebook page, there was another clue about the division between the factions.

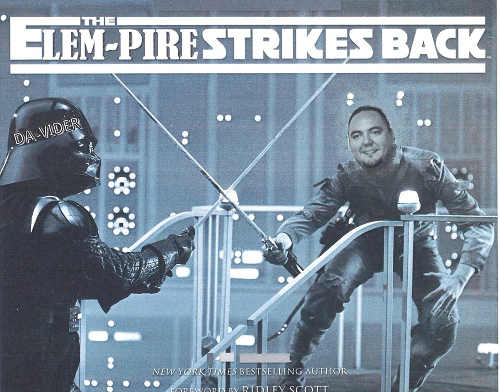

The page's main cover picture is an altered still from a Star Wars film, with Agustin Garcia's head imposed on the body of a Jedi. He is shown battling with a Darth Vader figure, whose helmet has “Da-Vider” written on it. Above the two figures are written the words, “The Elem-Pire Strikes Back.” The image appears to have been posted last April.

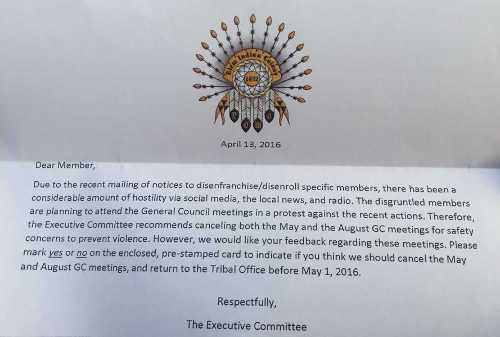

In an April 13 letter to members, the Elem Executive Committee said that since the disenrollment orders were issued there has been “a considerable amount of hostility via social media, the local news, and radio.”

With the “disgruntled members” planning to attend the general council meetings to protect, the committee suggested that the May and August general council meetings be canceled “for safety concerns to prevent violence,” and asked members to vote on an enclosed card and return it to the tribal office before May 1.

Offer to help settle the dispute

Elem has remained a nongaming tribe since its casino was closed in October 1995, at about the same time as a series of shootings and violent crimes swept the rancheria.

As a nongaming tribe, it receives $1.1 million annually from the Revenue Sharing Trust Fund. Created in 1999, that fund receives payments from gaming tribes in exchange for the ability to operate up to 2,000 slot machines, according to the California Legislative Analyst's Office.

Over the last several years, Elem's leadership has proposed a casino development in the Bay Area. That plan, headed up by Agustin Garcia and Anthony Cohen, who has worked as the executive committee's attorney and assisted on economic development project, was for the development of North Mare Island, which would have included a casino, shopping, dining, conference center, nature trails and more.

Citing health concerns due to mercury contamination from the nearby Sulphur Bank Mercury mine, the proposal said the tribe's traditional homelands have been rendered “worse than useless,” adding, “Elem is proposing to relocate and establish a new sovereign tribal homeland on Mare Island, pursuant to an intergovernmental agreement with the City of Vallejo and necessary federal approvals.”

However, in January 2015 the Vallejo City Council voted to focus on industrial – not casino – projects, which appeared to end the project proposed not just by Elem but a competing proposal by the Koi Nation, another Lake County tribe.

Boland said it's unclear who will be representing the executive committee in the lawsuit, as Cohen stated publicly on his Web site at www.tonycohenlaw.com on April 27 that he won't support the disenrollment action and that he intends to step away from all further work at Elem “unless/until the Tribe heals itself.”

He also offered, “If both sides of this dispute would like me to help to create a solution, I would be happy to do that.”

Roseville attorney Jack Duran, who specializes in tribal government, gaming and regulations, told the plaintiffs that he is handling cases pending before the Interior Board of Indian Appeals, Boland said, adding it's not clear if Marston will be involved.

Email Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. . Follow her on Twitter, @ERLarson, or Lake County News, @LakeCoNews.