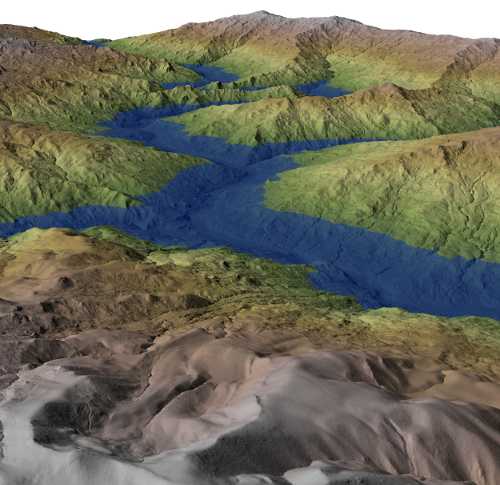

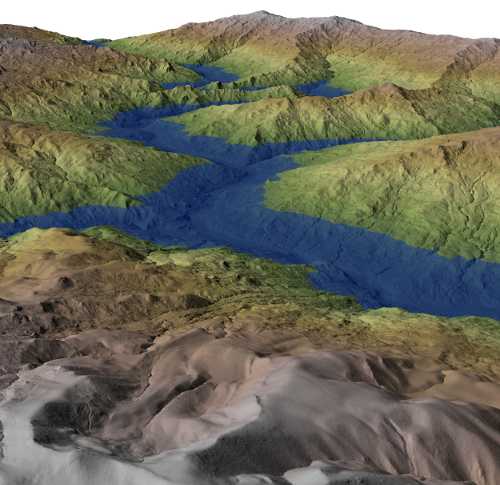

Northern California's Eel River at the site where a landslide dammed it thousands of years ago. Much of the evidence for the dam has been eroded over time. Credit: Ben Mackey, Caltech.

NORTH COAST, Calif. – A catastrophic landslide 22,500 years ago dammed the upper reaches of Northern California's Eel River, forming a 30-mile-long lake which has since disappeared.

However, a new report said that landslide left a living legacy found today in the genes of the region's steelhead trout.

Using remote-sensing technology known as airborne Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) and hand-held global-positioning-systems units, scientists recently found evidence for a late Pleistocene, landslide-dammed lake along the river.

Today the Eel river is 200 miles long, carved into the ground from high in the California Coast Ranges to the river's mouth in the Pacific Ocean in Humboldt County.

The evidence for the ancient landslide, which, scientists say, blocked the river with a 400-foot-wall of loose rock and debris, is detailed this week in a paper appearing on-line in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The research provides a rare glimpse into the geological history of this rapidly evolving mountainous region.

“This study reminds us that there are still significant surprises to be unearthed about past landscape dynamics and their broad impacts,” said Paul Cutler, program director in the National Science Foundation's Division of Earth Sciences, which funded the research. “For example, it provides valuable information for assessing modern landslide hazard potential in this region.”

It also helps to explain emerging evidence from other studies that show a dramatic decrease in the amount of sediment deposited from the river in the ocean just offshore at about the same time period, says lead author of the paper Benjamin Mackey of the California Institute of Technology.

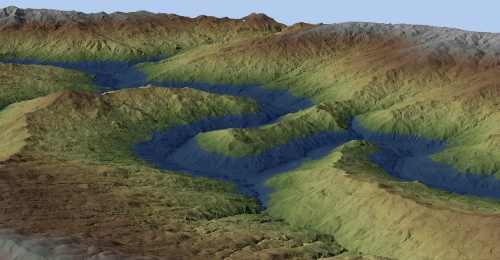

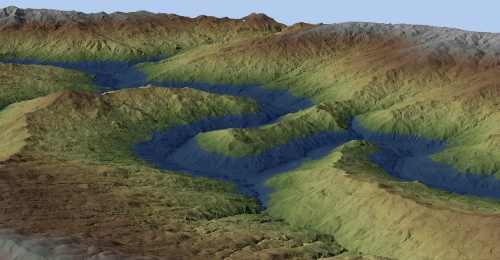

An artist's rendering of a view down Northern California's Eel River, with the reconstructed ancient lake surface in blue. Credit: Ben Mackey, Caltech.

“Perhaps of most interest, the presence of this landslide dam also provides an explanation for the results of previous research on the genetics of steelhead trout in the Eel River,” Mackey said.

In that study, scientists found a striking relationship between two types of ocean-going steelhead in the river – a genetic similarity not seen among summer-run and winter-run steelhead in other nearby waterways.

An interbreeding of the two fish, in a process known as genetic introgression, may have occurred among the fish brought together while the river was dammed, Mackey said.

“The dam likely would have been impassable to the fish migrating upstream, meaning both ecotypes would have been forced to spawn and inadvertently breed downstream of the dam. This period of gene flow between the two types of steelhead can explain the genetic similarity observed today.”

Once the dam burst, the fish would have reoccupied their preferred spawning grounds and resumed different genetic trajectories.

“The damming of the river was a dramatic, punctuated event that greatly altered the landscape,” said co-author Joshua Roering, a geologist at the University of Oregon.

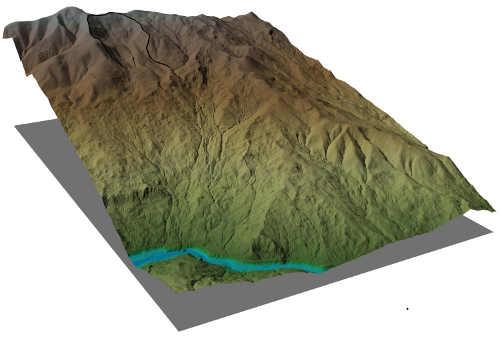

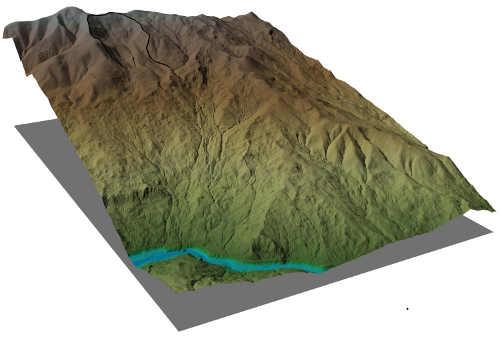

Nefus Peak, the source of the ancient landslide that formed the lake in what is today the Eel River in Northern California. Credit: Ben Mackey, Caltech.

“Although current physical evidence for the landslide dam and ancient lake is subtle, its effects are recorded in the Pacific Ocean and persist in the genetic make-up of today's Eel River steelhead,” said Roering. “It's rare for scientists to be able to connect the dots between such diverse phenomena.”

The lake formed by the landslide, the researchers theorize, covered about 18 square miles.

After the dam was breached, the flow of water would have generated one of North America's largest landslide-dam outburst floods.

Landslide activity and erosion have erased much of the evidence for the now-gone lake. Without the acquisition of LiDAR mapping, the lake's existence may have never been discovered, the scientists said.

The area affected by the landslide-caused dam accounts for about 58 percent of the modern Eel River watershed. Based on today's general erosion rates, the geologists believe that the lake could have filled in with sediment within about 600 years.

“The presence of a dam of this size was unexpected in the Eel River, given the abundance of easily eroded sandstone and mudstone, which are generally not considered strong enough to form long-lived dams,” Mackey said.

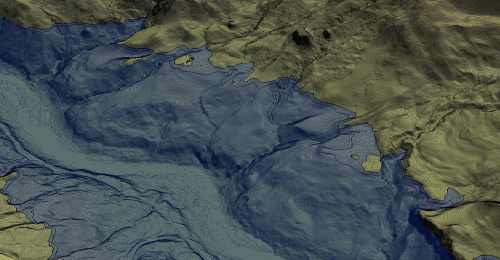

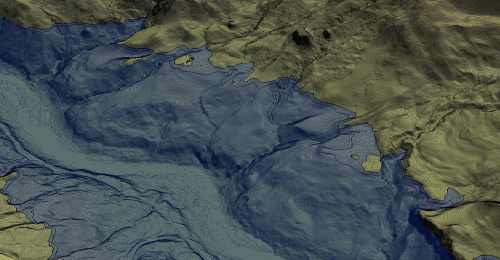

The modern Eel River is shown here, in blue. The landslide scar is visible in black. Credit: Ben Mackey, Caltech.

He and colleagues were drawn to the Eel River – among the most-studied erosion systems in the world- – to study large, slow-moving landslides.

"While analyzing the elevation of terraces along the river, we discovered they clustered at a common elevation rather than decreased in elevation downstream paralleling the river profile, as would be expected for river terraces," said Mackey.

“That was the first sign of something unusual, and it clued us into the possibility of an ancient lake,” Mackey said.

The third co-author on the paper is Michael Lamb, a geologist at the California Institute of Technology.

The National Center for Airborne Laser Mapping also provided LiDAR data used in the project.

Follow Lake County News on Twitter at http://twitter.com/LakeCoNews, on Tumblr at www.lakeconews.tumblr.com, on Facebook at http://www.facebook.com/pages/Lake-County-News/143156775604?ref=mf and on YouTube at http://www.youtube.com/user/LakeCoNews .

The lake's shore cut into the opposite hillslope, forming broad, flat areas shown in contours. Credit: Ben Mackey, Caltech.

Fine silt and mud were found upstream, indicating sediments in the still waters of a lake. Credit: Ben Mackey, Caltech.