- Elizabeth Larson

- Posted On

Veterans remember attack on Pearl Harbor

0745 hours, Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941

Shortly before 8 a.m. on the morning of Sunday, Dec. 7, 1941, 16-year-old Jim Harris was standing on the quarter deck of the USS Dobbin AD3.

Harris was part of the command allowance for the Com DES Flot 1 – which stands for Commander Destroyer Flotilla 1 – the group of men who traveled with the admiral.

The Dobbin was a repair ship and mother ship for destroyers. “We we would travel from ship to ship, as the flag travels,” he said.

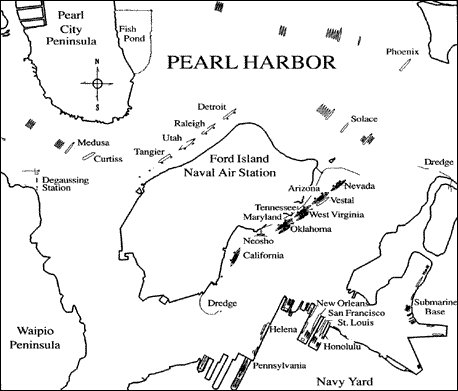

As he stood on the Dobbin that morning, across the way a church service and flag-raising ceremony was about to take place on the deck of the USS Arizona.

“I had just eaten breakfast, I was standing on the quarter deck when the first flight of planes arrived,” he said.

“We thought they were from the USS Enterprise, which we knew was returning from Christmas Island and Wake Island,” said Harris, now 83.

There, the Enterprise had dropped off Marines and Marine aircraft, said Harris, and the ship was expected back. According to a Naval chronology of the day, the Enterprise was indeed en route to Pearl Harbor, and had launched scout planes at 6:18 a.m.

But the planes that Harris saw come in over the 'Aiea Hills weren't from the Enterprise.

When the planes banked, Harris said, “We could see the red meatball.”

The “meatball” was a sailor's term for the red sun, the imperial seal of the Empire of Japan.

“After a few cuss words we identified them,” he said.

0750 hours

Seaman First Class Walt Urmann, 18, was on watch on the destroyer USS Blue DD387.

He had taken the flag from the quarter deck to the stern, where he was waiting for the ship's whistle to blow, the signal to raise the flag.

“At about seven minutes to eight I heard a horrible explosion over on Ford Island,” he said.

He looked up to see a Japanese plane, flying so low over the Blue's deck that he could see the pilot waving at him, and the big red suns on the side of the plane.

“I knew we were at war,” he said.

The pilot that waved at him had just dropped a torpedo that hit the USS Utah, said Urmann.

On the USS West Virginia, 23-year-old Fire Controllman Dean Darrow was getting ready to go on liberty in Honolulu, recalls his widow, Alice. Standing at his locker, he looked up and saw planes coming over, and heard the alarm sounded over the radio.

He later said that if he'd had a rock he could have thrown one and hit one of the Japanese planes, they were so close, Alice Darrow said.

Dean Darrow and his shipmates ran to get ammunition to return fire, only to discover the ammunition was locked up.

Seventeen-year-old WK Slater had joined the USS Pennsylvania in October 1941. On Dec. 7, the ship was in drydock. Slater, who said he was “just a deckhand,” was below decks when the bombs started.

At first he thought it was battle exercises, but that seemed unusual because it was Sunday.

Back aboard the Dobbin, Harris said the officer of the deck hit the alarm for general quarters and called all boats away, because many of the battleships had smaller boats tied to their sides, and couldn't move or do combat until those boats had moved off.

“We all got on the admiral's barge and came around to the ship's landing and took orders from the flag officer,” Harris said.

The admiral's barge moved around the USS Solace, a hospital ship anchored off the Dobbin, as well as two destroyers and the old Spanish American War battle cruiser Baltimore, which had been set to become scrap metal. The USS Nevada was tied at Ford Island, he said.

By 7:55 a.m. the Naval chronology said that the attack was well under way, with most of the ships having sounded general quarters.

0756 hours

On the Blue, Urmann said he and the other sailors rushed to their battle stations, and, like Darrow and those aboard the West Virginia, found the magazines locked. Urmann said they had to break the locks to get at the ammunition for the Blue's anti-aircraft guns.

Heavy shocks hit the West Virginia at 7:56 a.m.; Darrow said her husband's ship had been torpedoed. Naval records report that the West Virginia listed rapidly to its port side. That's when Dean Darrow went into the water.

He swam under the burning layer of oil on the water's surface, and came up on the other side. As he was being pulled from the water and into a boat by a group of rescuers, the Japanese planes began strafing the water's surface, Alice Darrow explained. A machine gun bullet struck him in the back and he was taken to the hospital.

0806 hours

Urmann said the Blue's guns got going at five minutes after 8 a.m.

Harris said the USS Vestal, a repair ship, had been moored to the port side of Arizona and was pulling away when both ships were struck. Naval records showed they were hit at 8:06 a.m.

The Vestal's captain was blown off the ship's bridge, said Harris. “We were in shock.”

As the admiral's barge made its way toward the captain, the man – still alive and swimming – waved them off toward the Arizona, said Harris.

“Stranger things happened,” he said.

0808 hours

“We started toward the Arizona to pick up survivors, and that's when she exploded,” said Harris.

The ship's two magazines ignited, creating what Urmann called a “horrible explosion.”

While Slater didn't see the Arizona blow up, “you couldn't miss it otherwise,” because it blew up for quite a while, he Slater.

By the time they got to the Arizona, “There were no survivors to pick up as far as we could find,” said Harris.

Most of those who survived the Arizona explosion were on liberty, Harris said.

Harris and his comrades made a number of trips, hauling survivors back to 'Aiea. At first, they had tried to take the men to the hospital ship Solace, but the men were covered with oil and couldn't get up the ship's polished staircase.

0840 hours

Urmann said it was close to 8:40 a.m. when the Blue got under way, after returning fire on the Japanese and shooting down two planes.

As the Blue moved out of the harbor, “They tried to bomb us all the way out,” said Urmann.

0906 hours

Shortly after 9 a.m., the Japanese launched a second attack, this time aiming for the ships in drydock, according to Naval records.

Aboard the Pennsylvania, Slater and his fellows were busy returning fire.

“My battle station was to take shells from a locker and bring them out to guys that were loading the gun,” he said.

A hoist used to bring the shells to the deck had broken down, so Slater said it forced he and other ammunition handlers to bring the shells up manually.

“When we were down getting those shells manually the one bomb that hit the ship went right through where my battle station was,” he said.

Naval records show a bomb hit the destroyer USS Downes in dock ahead of Pennsylvania. Another bomb then hit Pennsylvania's boat deck, a few feet from gun No. 7. The bomb passed through the boat deck and detonated near the No. 5 gun and the No. 9 casement. Pennsylvania still managed to hit two Japanese planes.

Slater said a number of men were killed by the bomb; had he still been on deck, he was sure that he would have been hit as well. “That's the most harrowing thing that happened to me that day,” he said.

Explaining how he felt, Slater said, “Frightened isn't the word.”

As he came up from below, Slater also saw that the Oklahoma had already rolled over.

Meanwhile, after 20 minutes, the USS Blue had managed to get out of Pearl Harbor, starting on patrol around the time the Pennsylvania was hit.

While on patrol, they got an underwater sound contact on a full-sized Japanese submarine, Urmann said and began dropping depth charges.

“We sunk that submarine but we never got credit for it,” he said.

However, they saw the oil and debris come to the surface.

Said Harris, “The whole attack must have gone over an hour and 20 minutes.”

1005 hours

A still-shaken Slater watches as the USS Shaw, also in drydock, explodes after it was first hit with a bomb at 8:15 a.m., according to Navy records.

While on patrol Urmann said the Blue met up with the USS St. Louis, the USS Helena and three other destroyers.

“We looked all the rest of that day for the Japanese,” said Urmann, who turned 84 on Nov. 27. “Luckily, we never found them.”

The aftermath of the attack

The following day, Monday, Dec. 8, the Blue linked up with the USS Enterprise, arriving back from Wake Island.

By 8 p.m. on Dec. 8 the Blue was back in Pearl Harbor. “We couldn't believe the damage that we saw,” said Urmann. “It was a mess.”

Naval records report that the Arizona, California and West Virginia were sunk at berth; the Oklahoma capsized, the Oglala was sunk by an aircraft torpedo, the Utah capsized and sank. Also damaged were the Maryland, Nevada, Pennsylvania, Tennessee, Helena, Honolulu, Raleigh, Shaw, Curtiss and Vestal.

The bomb that hit the Cassin in drydock caused it to fall off its blocks and onto the Downes.

The human toll was extreme. More than 2,400 Americans died in the attack, according to US Navy records.

Slater, who had gone to get something to eat at the enlisted club, was given a rifle and two bandoliers of shells by a big Marine and told to patrol the area around the hospital.

He said until that day he had felt safe amidst the might of the US Navy, but the “mouth dropping” effects of the attack changed his mind in a hurry.

As many as 24 men on the Pennsylvania were killed, said Slater.

After the attack, Slater said an officer gave him a pan with a pair of boots in it and told him to take it down and dump it in a trash receptacle off the ship. He said he looked down at the boots and realized a man's feet were still in them.

That night, three US planes came in were shot down by friendly fire, said Slater.

Wires had been put up to keep people off the lawns, said Slater. As he was patrolling that night he tripped over a wire, his rifle went up in the air and came down, hitting him on the head.

“The Japanese didn't get me that day but I did a pretty good job on myself,” he laughed.

Tomorrow, where they went after the attack and where they are today.

E-mail Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

{mos_sb_discuss:2}