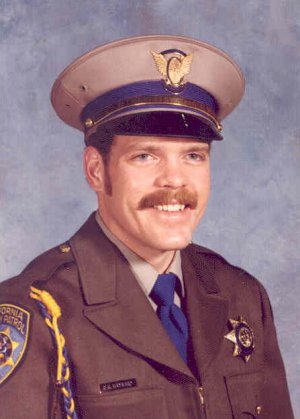

Lt. Dane Hayward was commander of the Clear Lake CHP office for the last seven years. His retirement became official on Sunday. Courtesy photo.

LAKE COUNTY – After 31 years as a member of the California Highway Patrol and seven years as commander of the CHP's Clear Lake office, Lt. Dane Hayward is retiring from the agency. {sidebar id=88}

Hayward, 60, is at the CHP's mandatory retirement age. But don't expect him to be sitting around on the porch.

Although his retirement from the CHP became official on Sunday, on Monday he starts work with the Lake County Sheriff's Office Boat Patrol. There, he'll get to put his love of boating and the water to good use.

“I've really enjoyed working with him,” said Officer Adam Garcia, who added that Hayward's involvement in the community is a model for others.

Officer Josh Dye offered his own perspective on his outgoing boss. “He's an interesting mix of progressive, new ideas and old-school philosophy.”

Succeeding Hayward on July 1 will be Lt. Mark Loveless, who's coming from Redding to take the position. Loveless isn't a stranger to Lake County, having served here as a CHP officer in the 1990s.

Hayward and his wife, Phil, plan on staying in Lake County. “It's very nice here. Nice people, excellent weather, no traffic,” he said.

He took over as the Clear Lake office commander in March 2001, following 24 years in offices around the state – serving in Los Angeles, West Valley, Venture and Baldwin Park.

In the three decades he's been in the CHP, Hayward has seen a major change in technology, with computers, radar, tasers and automatic weapons expanding the CHP's ability to protect the state's highways and roadways. Likewise, the agency is seeing its force of officers growing in both size and diversity, with more people becoming interested in working for the CHP.

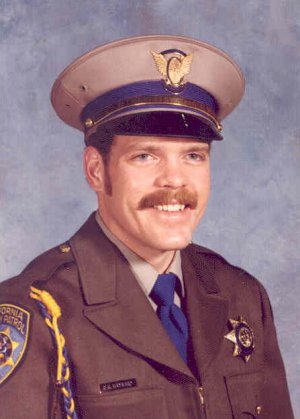

It was as a city policeman that Hayward got his start in law enforcement in the 1970s. After answering barking dog calls and reports of missing manhole covers for a year, Hayward decided he liked patrol best, and entered the CHP Academy in October 1977, graduating in February 1978.

When Hayward got his start, new CHP officers were still doing an obligatory term of service in Southern California. He worked in central Los Angeles until January 1982.

It was during his time there that he confronted one of his most life-threatening situations.

In 1980, a young man in the area who was turning 24 left a note to his father saying he was going to kill his wife and baby. Authorities were called and the CHP encountered the young man, who was armed.

Hayward was the fourth officer to roll up onto the scene. He said the young man shot at him and Hayward returned fire, killing him. It was a case, said Hayward, of “suicide by cop,” although that term wasn't applied back then.

Following his time in central Los Angeles, he took other assignments in Southern California, reaching the rank of lieutenant in 1997. In the midst of that, he managed to earn four lifetime college credentials, including a master's degree in psychology from the University of California, San Francisco, in 1989. He's used his psychology degree in his work as a CHP officer, and also assists with debriefings of first responders in tragic and stressful situations.

He wanted his own command, and when the Clear Lake office opened up, he came north.

After a year as a city police officer, Hayward joined the CHP in 1977, enjoying patrol and finding his new duties more interesting. Courtesy photo.

A commander's many responsibilities

As the Clear Lake office commander, Hayward said he was responsible for 1193 duties – literally – in the CHP manual, from reports and budgets to mounds of paperwork. He also continued to do enforcement, pulling over speeders and, as late as a few months ago, ramming a car in a pursuit as part of a maneuver to end the chase.

The Clear Lake office has 26 officers and 12 cars, one of the largest lieutenant commands in the state, he said. They patrol 867 miles of roads in Lake County, including seven miles of freeway. They're responsible for all roads in the county with the exception of those in the cities of Clearlake and Lakeport.

“We are consistently the second or third busiest area in all the areas of the Northern Division,” he said, with the Northern Division stretching all the way to the Oregon border, and including 17 commands.

The greatest misconception the public has about the CHP, in Hayward's opinion, is that it's law-enforcement driven, or all about handing out tickets.

Not so, he said. It's really about safety, and getting people to take responsibility for themselves while on the road.

For example, Hayward said the two biggest causes of fatalities the CHP sees – driving under the influence and not using seat belts – can be prevented. Take those out of the equation and you'll stop most highway fatalities, he said.

DUI isn't higher per capita in Lake County, he said. But the county does see an annual summer influx of visitors, going from a population of about 63,000 to 150,000 in the summer, numbers he said are increasing.

Last year Lake County had 16 roadway deaths, Hayward said.

In Lake County, as elsewhere, Hayward said many drivers fail to look far enough ahead – only focusing on what's in front of them or a few car lengths ahead – rather than keeping a farther visual horizon, which can help them spot hazards, especially on Lake County's winding roads.

One problem that is unique to Lake County are slower drivers, Hayward said, which is an outgrowth of the larger senior population. If you have five or more cars behind you, you must pull over to let them pass. That, he said, helps prevent people from becoming frustrated and making passes on dangerous curves.

If there's anything he doesn't like about his job, it's the “paperwork mass,” some of which was still stacked on his desk as he was preparing to vacate his office for the last time. The paperwork, he added, is “sometimes enough to drive you nuts.”

Hitting the retirement bubble

The CHP, which doubled in size in the late 1960s and early 1970s, is now experiencing a “retirement bubble,” said Hayward.

Many officers who, like him, joined during those years are now reaching the mandatory retirement age. He said that retirement surge – along with lack of retention in some cases – has resulted in 500 vacancies statewide. But he adds that vacancies and retention are an issue for all law enforcement agencies.

Unlike when he started, new officers can now bypass Southern California and start new assignments farther north. The Northern CHP Division, he said, hires four officers for every hundred applicants, which he said is higher than some other areas of the state.

Hayward said some of the traits he's noticed in CHP officers are a strong sense of right and wrong – or “a strong moral compass.”

While offering an exciting career with a lot of good benefits, there also are dangers when working on the state's roads and highways, said Hayward.

There is one statistic about the CHP that Hayward, with his psychology training, is especially keyed into, because he's received special training in it. That's the suicide rate.

In 2006, the CHP had the highest suicide rate of any law enforcement agency in the United States, said Hayward.

That year, there were eight CHP officers in the state who took their own lives, he said. While most law enforcement agencies have a suicide rate of 18.5 per 100,000, CHP's that year was 200 per 100,000.

Hayward has taken training called “Not One More Suicide,” which explores the issue.

The question of why is happens, he said, is the hardest to answer, because the people with the answer are gone.

Making Lake County a safer place

Hayward has taken seriously his job to make Lake County a safer place to live and drive.

His office has received awards for increasing use of child safety seats and reducing intersection collisions.

Looking back over his time as Clear Lake's commander, there are a few things Hayward points to when asked which of his achievements leave him with the most satisfaction – and both are about safety.

“I haven't lost an officer,” he said. “That makes me very happy.”

Then there's the Northshore pedestrian safety grant, which the CHP received in 2003 thanks to Hayward's efforts.

He took on the project after a little girl in Lucerne was killed early one morning in 2002 while walking to the school bus.

“That was it for me,” said Hayward.

The result was that CHP received a $500,000 grant to fund an additional 1,500 officer hours – 1,000 for CHP and 500 for the Lake County Sheriff's Office – to make the Northshore communities safer.

Caltrans also joined in the effort, spending another $500,000 to add a continuous turn lane through Nice, Lucerne and Clearlake Oaks; install flashing pedestrian safety signs; an add “piano key” crosswalks throughout the communities.

There hasn't been a pedestrian death since then, said Hayward.

He added that Caltrans has been an important partner in local highway safety efforts, and he's had an excellent working relationship with Charles Fielder, director of Caltrans' District 1 division, which includes Lake County.

Hayward, who is a member of the US Coast Guard Auxiliary Flotilla 8-8, loves time on the water, and says he's looking forward to a new assignment with the Sheriff's Boat Patrol. Continuing work with the public is a good fit, because he said he likes meeting people.

He's also looking forward to more time with his family, especially his 7-year-old grandsons, who live with his son in Ventura. The Haywards' daughter lives in Pennsylvania.

“It's been a wonderful experience,” Hayward said of his command at the Clear Lake office. “Couldn't ask for a better way to end your career.”

E-mail Elizabeth Larson at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it..

{mos_sb_discuss:2}