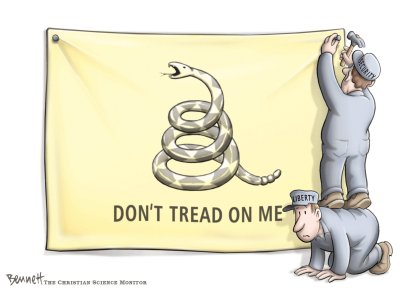

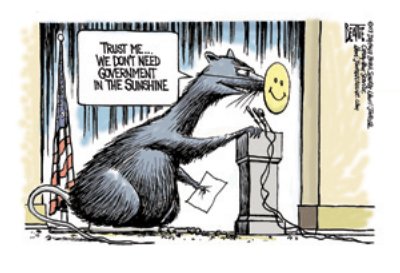

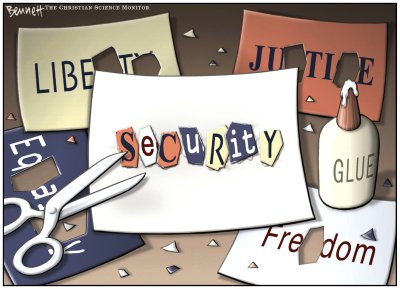

In reporters' role as the eyes and ears of their readers and as citizens seeking information from the government to improve or make more sense of their lives, there is a constant effort to acquire and process information from the government. Although that may be an easy task in some circumstances, it can be daunting in others. When there is a question, legal tools, particularly laws granting public access to government information often known as sunshine, Freedom of Information (FOI) or open meetings laws, can be especially useful. But how do you use them in the best way possible?

FOI Laws

Requesting Records: In many instances, you simply pick up the phone or walk into government offices and ask for the records of your interest. Often that is enough to gain access. If that fails, before getting off the phone or leaving the office, it is suggested that you might say something like "Well, I guess I'll have to submit a FOI request." Sometimes the suggestion that a FOI request may be made is enough to free up the records. If that fails, you submit your FOI request in writing.

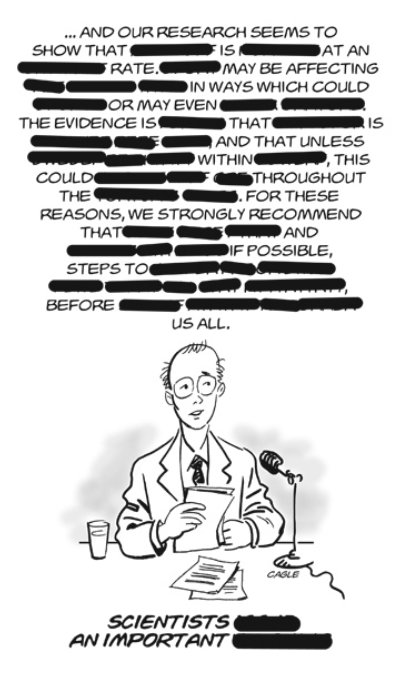

How to Request Records: First, the title of the law, Freedom of Information, may be somewhat misleading. It is not a vehicle that requires government officials to answer your questions. While they may and often do so, there is no legal obligation to provide responses to your questions. An FOI law generally deals with existing records and does not require that a government agency prepare a new record in response to a request for information.

When making a request, FOI usually requires that you provide sufficient information to enable staff to locate the records of your interest. Whether a request reasonably describes the records may be dependent on the nature of an agency's filing or record-keeping system. If you are unsure of what you want or how the records are kept (i.e., by name, street address, or perhaps chronologically), ask. Often agency staff must assist in enabling you to make a proper request.

Delays: Many are familiar with the old adage, "Access delayed is access denied." Although an FOI law does not require that agencies jump in response to a request, it is generally intended to require that government agencies make records available whenever and wherever feasible. If you walk into the clerk's office and request the minutes of last month's meeting, often the clerk will simply say, "Sure, they're over there." When an instant response cannot be given, FOI laws usually require that agencies respond in some manner within a certain number of days.

When a request is denied, most often you have the right to appeal to the head or governing body of the agency or the person designated to determine appeals.

Going to Court: If an appeal is denied, you can challenge the denial in court, and FOI laws usually require that the government prove that the records were withheld with justification. NOTE: FOI laws are generally based upon a presumption of access and require that all agency records be disclosed, except those records or portions of records that fall within a series of exceptions to rights of access. Most of those exceptions are based upon the potential harm that would arise if the records are disclosed. When agencies are sued, they often must prove that the harmful effects of disclosure would indeed arise. (That means that they should invoke the Aretha Franklin principle: not "R-E-S-P-E-C-T", but rather "You better think!" before denying access).

If agencies do not meet their burden of proof and you substantially prevail, a judge under many FOI laws may award attorney's fees to you, payable by the agency.

Myths: How many of you have heard something like, "This is a personnel matter. We can’t disclose," or "It's in litigation. We can't discuss it," or "It's under investigation. Sorry, you can't see anything!" None of those statements is true. What they are really saying is, "We don’t want to talk about it." Sometimes it's laziness, and in others, it's the possibility of embarrassment that underlie those statements. Remember: embarrassment is not one of the grounds for withholding records under an FOI law, and it's not one of the grounds for closing meetings under an open meetings law.

Personnel Records: Some aspects of personnel records may justifiably be withheld (i.e., public employees' Social Security numbers, medical information and other items that are unrelated to the performance of their duties). However, other items concerning public employees are typically accessible, including their salaries, overtime pay, gross wages, attendance records, qualifications for the position that they hold, general educational background and, in most cases, disciplinary actions taken against them. You should always challenge a denial of access when you are told that the materials are being denied because they are personnel records. Some aspects of those records are public; others are not.

Litigation: Records indicating legal advice given by a government attorney to government officials may be privileged. However, when litigation has commenced, anyone can walk into the courthouse and usually obtain any of the records that have been filed with the court. Although FOI laws often do not apply to courts, most court records are typically available under other provisions of law.

Investigations: When a crime is committed, portions of records might justifiably be withheld, but others typically must be disclosed. We don't have secret arrests in this country, and the items contained within booking records are usually available. If no arrest has yet been made and the matter is under investigation, records can be withheld insofar as disclosure would interfere with an investigation, deprive a person of a right to a fair trial, or, for example, identify a confidential source. But the fact that a crime has been committed usually requires the disclosure of some portions of law enforcement records.

Open Meetings Laws

What is a Meeting? Everyone has heard the phrase "a rose is a rose is a rose." In most states, a meeting is a meeting is a meeting. When a majority of a government body, such as a town board, a board of education, a planning board, or a city council, gathers for the purpose of conducting public business, that gathering is a "meeting" that falls within the coverage of an open meetings law. It usually doesn't matter whether there is intent to take action or what the gathering is called. A "work session" or "workshop" conducted by a government body is a meeting.

Executive Sessions: An executive session or its equivalent is most often a portion of an open meeting during which the public may be excluded. Most open meetings laws specify and limit the grounds for entry into executive session.

Personnel: When speaking before the National Association of School boards, I asked the crowd: "What is your favorite word for entering into a closed session?" The resounding response was "personnel!" Nevertheless, often that term is a catchall. It's a trap. It's a word that should be eliminated from everyone's vocabulary.

Some personnel matters may be discussed in private, but many others must be discussed publicly. Often the language of the law is precise and authorizes a government body to conduct an executive session to discuss certain matters as they may relate to a particular person, rather than staff generally.

If a board is discussing the budget and whether positions should be retained or eliminated, the focus would not pertain to any particular person. Even though it may be a personnel matter, there would be no basis for going into executive session, for the issue would involve issues of policy (how public money should be allocated, or whether a position is needed).

On the other hand, if the discussion involves whether to promote or fire a specific person, an executive session might properly be held. In that case, the focus would deal with "a particular person" in relation to his or her performance.

Possible Litigation: The courts have held in some states that the litigation exception for entry into executive session is intended to enable a government body to discuss its "litigation strategy" in private so as not to divulge its strategy to its adversary, who may be present at a meeting. They have also held that the threat, the fear, or the possibility of litigation is not enough to justify an executive session. If it were, there would be little left of an open meetings law.

What to Do? What if it doesn't appear that there is a proper basis for going into executive session? What do you do? First, you should have your copy of your state open meetings law with you at all time. And then you invoke the "Tracy Chapman principle of law" (I think she had the best song of the '90s): "Baby just give me one reason, and I'll turn back around." You show the grounds for entry into executive session to the board and ask: "Please tell me where this subject fits." If it doesn’t fit, the board must discuss the issue in public. If you don't raise the question, often nobody else will, and the information may be lost forever.

In some states, there are government agencies created to deal with open government laws, and they are there to be used, and (for those knowledgeable in music trivia) you should invoke the "Bill Withers principle of law": "Use me – until you use me up." They are there to be used. In others, offices of attorneys general or news media associations may be able to offer guidance.

For an idea of what some government "sunshine" agencies do, you can look at the Web site of the New York Committee on Open Government. Just search online for "Committee on Open Government" or "COOG." Last year, in addition to receiving thousands of telephone inquiries and preparing hundreds of legal advisory opinions, the Committee’s Web site (http://www.dos.state.ny.us/coog/coogwww.html) received more than 1.8 million hits from more than 100,000 visitors. For a pretty good sense of what a sunshine agency does, check it out.

Robert J. Freeman is executive director of the New York State Committee on Open Government in Albany.

{mos_sb_discuss:4}